Excerpt from: Estelle Shohet Brettman, Vaults of Memory: The Roman Jewish Catacombs and their Context in the Ancient Mediterranean World (link), rev. ed. Amy K. Hirschfeld, Florence Wolsky, & Jessica Dello Russo. Boston: International Catacomb Society, 1991-2017 (rev. 2024).

Galleries

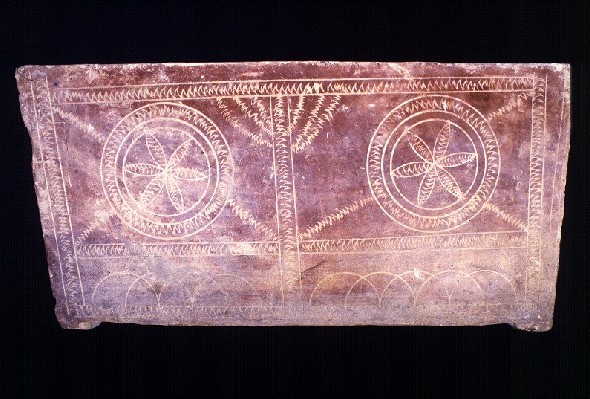

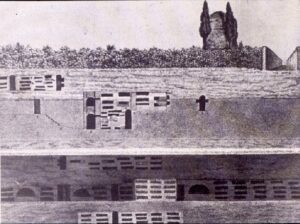

Fig. 1. Multi-Leveled City of the Dead: Cross section drawing of the Catacomb of Callixtus. After a design by De Rossi in Roma Sotteranea christiana descritta ed illustrata, II (Roma, 1864-1877), Tav. 51 and 52 (DAPICS n. 0523).

The volcanic nature of the earth around Rome, mostly consisting of a variably soft stone called tuff (tufa), made the terrain well suited for catacomb burial. It was relatively easy to dig tunnels for galleries and to incorporate existing hypogea and other excavations under the ground, such as arenaria (sandpits or quarries of pozzolana, a fine-grained tuff) and water conduits.[1] The nature of the resulting structures depended upon the degree of expertise of the craftsmen involved, the boundaries of the designated land,[2] and, in the case of private ownership, the social and economic status of the proprietors.

Entry to a catacomb was generally by an access stairway from an atrium or chamber that lead to a main passageway intersected by a grid of corridors. As space for more burials was needed, additional levels and corridors were excavated, and consequently some catacombs became vast networks of such passages. Another technique employed to create more space was to lower an existing gallery floor so that more loculi could be added beneath those already in the gallery walls.

The first level of a catacomb was generally dug three to eight meters below the surface. Sometimes there were as many as four levels reaching a depth of twenty to twenty-five meters, and a few catacombs, like those of the Giordani and Callisto, were laid out on five different levels. In contrast, the Jewish catacombs were on the whole simpler in elevation, consisting of one level or, at most, two, as in the catacombs of Monteverde and Vigna Randanini.[3]

The ground into which the catacombs were hewn consisted of several types of tuff, the most suitable layers being, naturally, the ones most extensively utilized for carving out catacombs. The layers could include fine pozzolana, lithoid tuff (hard, stony, and excellent for construction, but difficult to dig), and compact tuff. The Monteverde cemetery had been excavated in a four-meter-deep tufaceous stratum (called granular tuff by Muller) between a two-meter upper stratum of "humus" or dirt and a lower stratum of lithoid tuff. The continuous exploitation of the lithoid level for its valuable building material was the prime culprit in causing the collapse of the catacomb situated above it.[4] The Catacomb of Vigna Randanini was dug, for the most part, in fine pozzolanella, but some upper sections of the galleries reached the stratum of poor quality granular tuff, like a private hypogeum on the opposite side of the via Appia Pignatelli that is now inaccessible.[5] The Torlonia catacombs were carved out of no fewer than nine different geological strata lying one below the other in an area well populated with quarries and other underground tombs.[6]

The galleries of the catacombs could extend for many meters, and were covered by flat or vaulted ceilings.[7] The galleries averaged about two to three meters in height, and about one meter in width, but great variations occurred, dictated by factors such as the quality of the soil, preexisting construction, and the need or desire to accommodate more burials.[8] In some catacomb regions, particularly in those thought to have developed from arenaria, including parts of the Vigna Randanini, Labicana, Monteverde, and Priscilla cemeteries, the corridors were wider and somewhat curved.[9]

Light in the Depths

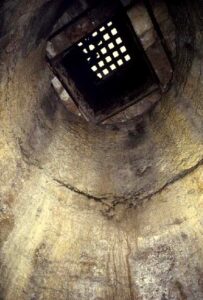

In the deep subterranean passages of the catacombs, illumination was provided for in various ways. Surface apertures known as lucernaria or luminaria admitted light as well as air. Openings which originally had been used for removing the earth during the construction of a catacomb could be adapted for this purpose. Depending on the depths of the cemetery, these light shafts might penetrate several levels.

Fig. 3. Detail of a lucenarium or skylight from the inside with a grate covering the square hole. This surface aperture served to light and air the dark passageways of the catacomb. Catacombs of Randanini, Rome (DAPICS n. 0199).

The light coming from such shafts into the depths of the earth is described to dramatic effect by Prudentius, a late fourth century Spanish courtier and public servant. He wrote of his visit to the subterranean shrine over St. Hippolytus' tomb in this way:

"Not far from the city walls among the well-trimmed orchards, there lies a crypt buried in darksome pits. Into its secret recesses a steep path with winding stairs directs one, even though the turnings shut out the light... and when, as you advance farther, the darkness as of night seems to get more and more obscure throughout the mazes of the cavern, there occur at various intervals apertures cut in the roof which convey the bright rays of the sun upon the cave. Although the recesses, twisting at random this way and that, form narrow chambers with darksome galleries, yet a considerable quantity of light finds its way through the pierced vaulting down into the hollow bowels of the mountain. And thus throughout the subterranean crypt, it is possible to perceive the brightness and to enjoy the light of the absent sun".[10]

Artificial light was provided by oil lamps, many bearing motifs compatible with the imagery in the catacombs. The lamps, set in niches cut into the walls of the corridors or affixed to the mortar seals of individual tombs, not only provided light in the catacombs, but had a cultic significance just as the lighting of lamps or candles does today. The ancient Egyptians had practiced the "glorification of the blessed [the deceased]" in a procession with flaming torches which were deposited with other offerings at the statues or graves of the departed.[11] Similarly, it was customary among some Romans to arrange for the "lighting of lamps at the grave on the Kalends, Ides, and Nones of every month".[12] The ancient Jews placed a candle or lamp near the head of the deceased, not only before burial, but also for seven days afterwards.[13] This ceremony might relate to Proverbs 20:27: "the spirit of man is the lamp of the Lord;" the light, perhaps, meant to symbolize the spark of the divine.

In the Villa Torlonia catacombs, more than one hundred lamps or their fragments have been documented.[14] Muller counted about one hundred lamps and fragments of lamps in the Monteverde catacomb, many of them found in tombs "above all near the head of the deceased." He opined that others found in the ruins of the chambers had "indubitably" been located in tombs, assuming that, since their spouts were blackened, they must have been lighted when placed in the tomb: this may, however, only indicate that the lamps had been lit at some point after their manufacture. Garrucci recorded one discovery of a lamp at the Vigna Randanini catacomb and also a "utensil... impressed above with a candelabrum" that he speculated was a thymiaterion for burning incense.[15]

Cubicula (Chambers)

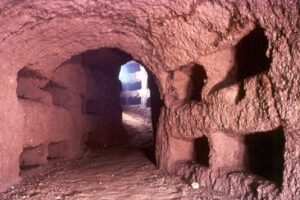

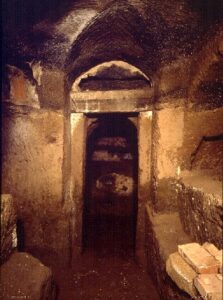

Fig. 5. General view of the anteroom to cubiculum I in the Catacombs of Villa Torlonia. Doorway and loculi cut above the doorway can be seen (DAPICS n. 0665).

Opening off the catacomb galleries were cubicula, either single chambers or interconnected rooms with simple thresholds and door jambs, rarely fitted with doors in-between. Sometimes a chamber was decorated with engaged columns on the interior walls or flanking the entrance, which, upon occasion, might be surmounted by a gable. The rooms were square, polygonal, or round, with their ceilings flat or vaulted, like those in the galleries. The walls and ceilings often were painted in fresco or tempera techniques.[16] Such chambers generally belonged to funerary associations or particular sects or, especially when lavishly decorated, to members of affluent families.

There are more examples of cubicula in pagan and Christian catacombs than there are in Jewish ones. In the Catacomb of Monteverde, the relative paucity of chambers perhaps be attributed to the convenience of using the "grottoes" and "recessed annexes" that Muller described for burials.[17] Of the six chambers revealed in three different Torlonia excavation campaigns from 1919-1973, five were hewn in the upper catacomb, and only one in the lower. These figures emphasize the different design and situation of the two adjoining sites.

Burial Types

In the Monteverde catacomb, Muller identified "no fewer than eleven" types of burial, but Rutgers has pointed out that in the Jewish catacombs of Rome as a whole, there are only in fact a few basic forms of interment and their variations.[18] The type of grave chosen no doubt depended on a family or individual's prosperity, the location of the grave, and the habitual preferences or methods of the gravedigger or fossor who carved it out.

Fig 6. Gallery intersection marked by a column carved into the tuff. Catacombs of Domitilla, Rome (DAPICS n. 0533).

Loculus and Trench Graves

The most common grave forms in the Jewish and Christian catacombs is the loculus, a horizontal, oblong niche in a wall, and the trough or trench-grave ("sepolcro a fossa"), a similar rectangular hollow carved into a floor.[19] Its name, a diminutive form of the Latin term locus, and meaning "small place," was a designation for the site of a grave. Since these types appeared in what seemed to Muller to be the oldest parts of the Monteverde catacomb, he considered them to be the earliest types of grave in the site.[20]

The loculi usually were usually superimposed one above another, and organized into vertical rows, sometimes a dozen units high or more, as was noted in some galleries of the Monteverde catacomb. Generally, however, the rows were fewer, and depended on the varying heights of the galleries.[21] In the Monteverde and Villa Torlonia cemeteries, the tomb stacks on the whole were no higher than four to eight loculi. The Randanini catacomb galleries, often lower in height, had four or five stacked openings per wall segment. Taller ranks of superimposed niches demanded all the expertise of the fossores to prevent a weakening of the walls.

Children's burials most often were accommodated by smaller loculi in pilae or tiers. Separate clusters of the children's loculi are noted at the corners of galleries or other weak points.[22] No doubt they also testify to the high infant mortality rate at this time.

Loculi for adult burials on average measure six feet in length, one foot in height, and one and a half feet or thereabouts in depth, as calculated by H. J. Leon in the Randanini and Torlonia catacombs.[23] Depending on the number of bodies which it contained, a loculus was termed monosome, bisome, trisome, quadrisome, or by the general term of polysome. Normally, a loculus for a Jew would hold one body, but there were variations, such as the use of pre-cut loculi of adult size to accommodate the burials of children in the Villa Torlonia, which were separated from each other in the same slot by a vertical tile or masonry divider.[24] Rabbinic (Halakah) instruction forbade the mingling of bodies with the burial of two or more people without separation, or the placement of a body next to another person's bones, but it is not possible to see this rule applied with consistency in the catacombs of Rome used by Jews.[25] At least one example of a polyandrion (grave for more than one individual) was identified by Muller by the entrance stairway into the Monteverde catacomb, and Fasola identified many loculi with arched ceilings, which he called "loculi ad arcosolio" in certain galleries of the lower catacomb of Villa Torlonia, usually near floor level, which seemed to have been used for two burials, one above the other, separated by a tile shelf, a practice also seen in the arched niches of masonry in one of the outer vestibules of the Vigna Randanini site.

Loculi Sealings

Two explorers of Jewish catacombs, Antonio Bosio in the early seventeenth century and Nikolaus Muller three centuries later, observed that the loculi in Jewish catacombs were typically sealed in a vertical direction with layers of tuff and mortar often covered by a layer of lime or clay and plaster that filled the interstices and revetted the entire face of the sealing walls. On the sealed covers, epitaphs could be painted or incised, as they were also on the less-frequently used coverings of plastered bricks, slabs of marble, and clay tiles.[26] This type of closure was observed in the Monteverde, Vigna Randanini, and Villa Torlonia sites,[27] as well as in the Jewish catacombs of Venosa in Southern Italy.[28]

Fasola recognized an exception to this burial practice in the upper-level galleries in the Villa Torlonia cemetery, in which the majority of the loculi were found to be sealed with tiles, but without the layer of plaster over them, resembling, in this way, the method of closure commonly employed in non-Jewish catacombs in Rome. This feature was one of the reasons why Fasola dated the upper areas of this catacomb later than the lower levels, where the conventional tuff closures were used.[29] Another infrequent type of sealing occurred in the Catacomb of Monteverde where, in some instances, the closure was an unusual combination of masonry wall and brick slabs embedded in this wall or placed behind it.

Marble slabs used for epitaphs in the Jewish catacombs could be affixed over the tomb opening or on the wall next to the tomb, and engraved or painted in red, perhaps with a mineral pigment like iron oxide. In the Randanini cemetery, there were examples of epitaphs placed upright at the head of the deceased in the tomb.[30] For those laid to rest in kokhim (see below), which were sealed with stone and lime plaster, the marble epitaphs were placed above the closure, or in the wall in a designated panel.[31]

In the Christian catacombs, the loculi commonly were sealed with slabs of marble, flat tiles, or bricks or blocks of tuff affixed with lime mortar. Tiles and bricks could be covered with plaster, but it was not the general rule. As in the Jewish catacombs, religious motifs and epitaphs (when present) were carved, painted, or scratched onto the closures or on the fresh lime plaster, when applied. Also common in the catacombs was the practice of reusing slabs from other burials, whether from pagan tombs or those of co-religionists.

Fig. 9. Wall painting of two birds with a floral garland in their claws. Graffiti can also be seen. Cubiculum II, Catacombs of Vigna Randanini, Rome (DAPICS n. 0012).

Arcosolia and Kokhim

Arcosolia are arched niches, generally larger than loculi, carved into the walls of catacombs in both chambers and galleries.[32]

As in Roman Palestine, where arcosolia often were carved out of each of the three unbroken walls of a funerary chamber, the Italian and Sicilian catacombs contain many examples of chambers lined with such tombs. Below the flat surface of the floor under the arch, one or several trough or trench graves might be cut.[33] An arcosolium could hold multiple burials, no doubt for spatial as well as financial economy.

In addition to the use of trench-graves in arcosolia, the body of the deceased or a receptacle into which the body had been placed, in the form of a wooden, stone, or clay casket (solium), might be laid on the floor beneath the arch or on a bench or shelf upon the floor called a mensa ("table").

Five arcosolia were described in funerary chambers inside of the Vigna Randanini catacomb. Fr. Fasola found more than thirty arcosolia in the chambers and galleries of the upper catacomb of Torlonia, but only two in the lower catacomb. The greater use of these extravagant structures in the upper catacomb of Villa Torlonia might point to a larger number of affluent individuals buried in this site, or a standard feature of its planning. In the upper catacomb, also, Fasola noted that many of the arcosolia were similar to those in Christian catacombs, hewn with higher arches that provided space for the construction of masonry tombs on top of the mensa.[34]

The proportionally small number of arcosolia observed in the Monteverde catacomb might suggest that the Jews buried in that cemetery were also of more moderate means than those in other sites. As the need later arose for more graves, the back wall or even the vault of an arcosolium might be further exploited by carving out loculi, causing damage to any decoration in the lunette under the arch.

An unexpected find of an intact sarcophagus below the back wall arcosolium in Painted Room IV in the Randanini catacomb led Garrucci to remark: "It is very rare to find an arched tomb, with a beautiful gilded sarcophagus placed under it, in which the arch was cut a long time after the construction," although the wish to place the sarcophagus there might very well have been the reason why the later modification was made.[35]

Marucchi described one example of an "arcosolio a nicchia," an arcosolium with a curved recess for its back wall, in the via Labicana catacomb. The inscription on a tomb of a similar form in the ancient Jewish cemetery of Venosa described it as an absis.[36]

The arcosolium evolved under Hellenistic influence in Palestine beginning in the first century BCE. It provided a more elaborate kind of burial arrangement in Palestine in addition to an already existing rectangular type of tomb called a kokh, a tunnel-like shaft cut perpendicularly into a wall, piercing the wall surface with its narrow end. At times, both types of tombs, arcosolia and kokhim, were hewn next to each other in Hellenistic and Roman catacombs in such sites as Jerusalem and Gezer.

The kokh, cut as a niche perpendicular to the wall of a gallery or chamber, was characteristic of rock-cut tombs in Palestine, though not exclusive to Jews. When found on rare occasion in Rome, it seems to be in reference to Near Eastern or African tomb design.[37] In the Mishnah, the post-Biblical body of Jewish law, the specifications for the kokh are set out: one cubit wide, slightly more than one cubit high, and four cubits deep. The cubit, an ancient unit of measure based on the length of the forearm from elbow to fingertips, was about eighteen to twenty-one inches long.[38] The niches of Palestine were greater in height than in width, and Klein suggested that it was to allow the lid of the coffin to be raised in the first few days after burial to assure that the departed, laid out on a pillow and covered by a blanket, was truly dead.[39]

Fig. 12. A close-up view of the interior of a kokh. Human bone fragments are visible. Catacombs of Vigna Randanini, Rome (DAPICS n. 0088).

Commenting on the resemblances between Jewish and non-Jewish graves in Rome, Leonard Rutgers observed that tombs in cemeteries for different religious groups are virtually identical, except for kokhim in the Jewish sites. Even in this context, however, examples of kokhim in Rome are few, with a significant presence only in the Vigna Randanini site.[40] Rutgers also noted that the Jewish kokhim were cut at the level of the floor, while the variation called "a forno", more common in Rome's non-Jewish cemeteries, was inserted at a higher level into the wall.[41] The ceilings of the kokhim in the Vigna Randanini catacomb were sometimes arched so that there was enough room to accommodate superimposed burials, divided by a ledge or with an elongated shaft to fit more bodies, though it is not clear if this was routine practice in the site.[42] Lateral additions to some kokhim created a cruciform configuration of shafts in a single tomb, or tombs back to back. There is one example of a kokh that was expanded into a multi-leveled hypogeum in miniature, with steps leading down from a kokh shaft to a lower chamber containing loculi and additional kokhim.[43]

Another type of tomb described by Garrucci in certain chambers of the Randanini catacomb was a grave in the form of a chest, carved under an arch and projecting "half-way out of the living rock." This type of grave was covered with large slabs of marble, with or without inscriptions.[44] De Rossi wrote of a similar structure carved from the wall of a chamber in the early "Hypogeum of the Flavii" in the Domitilla catacomb, calling it a "primordial monument of Christian cemetery architecture".[45] The entrance to the chamber was low and narrow, like that of a kokh, and, to de Rossi, the restricted opening and the burial structures within the chamber suggested the "genesis of (the Christian) funerary cubiculum from the Jewish sepulchral room".[46]

A type of burial economical of space was a multi-leveled trench or trough grave known as a “forma” tomb. Formae were cut into the floors of the cubicula and galleries and held several superimposed bodies separated by tiles. They might have been used not only because of a general shortage of space in a given site, but also to allow more of the faithful to be entombed near the graves of venerated persons; in the case of Christians, these included popes and martyrs, though it is hard to imagine a similar motive being employed in Jewish sites, even if certain figures were revered by the Jews in Rome as holy people or sages.

In the floor of the Randanini catacomb, many formae were found intact because these graves and the lower tiers of loculi were concealed from vandals by layers of sediment deposited by infiltrating rain water. Garrucci described graves covered with tile gables or horizontal slab-closures, including inscribed marbles, and graves cut into the angle were the wall meets the floor.[47]

The name "forma" was also given to a type of collective tomb built of bricks and resembling on the exterior a sarcofago murato (a masonry casket: see below). On the interior, the cavity was divided by a series of roof tiles resting on projecting bricks so that bodies could be interred one above the other in a vertical row. It was a type of tomb seen fairly often in Christian burial sites, either above or below the ground.[48]

Masonry Tombs

Masonry or built tombs were in use as early as the late fourth millennium in Early Dynastic Egypt as superstructures erected over graves in the ground.[49] They also existed in the Bronze Age Aegean area, in Phoenicia and her colonies, and in Archaic and Classical Greece.[50] The form was perpetuated through succeeding periods in the Mediterranean area. In some instances, masonry tombs evolved into sumptuous monumental structures in such regions of Asia Minor as Lycia, Persia, and Caria. The lavish Caria tomb of Mausolus bequeathed the term "mausoleum" to all such house-like or temple-like tombs of elaborate proportions and decoration in the Hellenistic and Roman periods throughout the entire Mediterranean region.

In the Monteverde catacombs, masonry tombs rose on top of the soil and, in many cases, above trough-graves that were mainly in the floors of the "grottoes," "recesses," and chambers. Muller considered them to be later burials, apparently not in use until interment had all but ceased in the site. Two kinds of built tomb were used in the Monteverde catacombs. One was a tuff and lime-mortar masonry chest, covered by slabs. In this type of tomb, the catacomb floor enclosed by the walls of the chest might serve as its bottom; the masonry walls and bottom could be plastered smoothly inside and out so that the chest somewhat resembled a sculpted stone sarcophagus. Slabs with pagan or Jewish inscriptions have been found used as bottoms and covers for some of these tombs, but even in this context it is difficult to determine whether they were intrusive, were dispersed epitaphs, or were recycled from other burials, as was often the case in catacombs in Rome.[51] Muller noted that even though the coffins in masonry, which were generally covered with roof tiles, were found in the grottoes near the entrance, they had placed there over an extended period of time.[52]

A second type of masonry tomb in the Monteverde catacombs consisted of a number of superimposed sarcofagi murati ("walled tombs"). The base of the upper tomb was the cover of the lower grave. The grottoes and annexes were found in many places crowded with piers of these superimposed burials, in one case, even reaching to the ceiling of one of the oldest grottoes.[53] The tufaceous walls of recesses and rooms thus could be directly incorporated as the walls for these structures. By burrowing into the tuff, and adding interior partitions, tomb builders could extend the sarcofagi murati to receive more than one adult body. Muller found that children's loculi more often than not contained multiple burials. The state of preservation of the structures was so poor, however, that Muller was unable to determine whether the bodies were "separated by means of slabs or thin walls (of masonry)."

Similar chest-like or marble-revetted masonry tombs were reported on the landing of the entrance stairway of the Villa Torlonia catacomb.[54] In the upper Torlonia catacomb, masonry tombs were also added to arcosolia that had been built with higher niches to accommodate extra tombs.[55]

In the small Jewish catacomb on the second mile of the via Labicana (now the via Casilina), archaeologist Orazio Marucchi found masonry tombs in several chambers and in two short lateral corridors. He referred to them as the "sepolcri in costruzioni". The two blind corridors, along with three others, perhaps served as hybrid gallery/chambers, used as modest burial crypts for several people who were related or otherwise associated.[56]

An allegedly singular form of burial was found near the stairway to the lower level of the Monteverde cemetery. Muller describes it as an earth mound "covered with a layer of grey lime" and "fashioned like the flat chest for the dead" in contemporary use in Italy, but in the shape of a trapezoid instead of a rectangle.[57]

Sarcophagi and Other Receptacles

Tub-shaped terra-cotta burial chests had been used in the Late Bronze Age Aegean area and in Late Archaic Greece.[58] After about the sixth century BCE, clay coffins appeared in many other areas of the Mediterranean, including Etruria and the Greek West. Later, in the Common Era, clay receptacles were in use in Phoenician sites, on the Syrian coast, and in cemeteries of Palestine, such as Beth She'arim, as well as in Italy.[59]

The use of coffins marked a change in Jewish burial practice. In Biblical times, the dead were not normally enclosed in any form of coffin. The bodies were carried on biers to their final resting places.[60] Jesus was laid to rest in a rock-cut familial tomb shrouded in linen.[61] Joseph's burial in a coffin was considered an aberrant custom borrowed from the Egyptians.[62] Not until Talmudic times did the coffin become part of the Jewish funerary equipage, and then only for the prosperous few who embraced the fashion. While a number of decorated coffins and coffin fragments, usually of marble, were found in the Jewish catacombs of Rome, greater numbers have been found in Christian and pagan burial grounds and in the Jewish crypts of Beth She'arim, where they were made of limestone, marble, and lead.[63] Because of vandalism in most of these sites, it is difficult to draw definite conclusions about the reason for the lesser number of marble coffins found in the Jewish catacombs, but by comparison, the known remains support the impression of a lower economic status for many Jews in Ancient Rome.

A number of clay coffins were uncovered in the Monteverde and Vigna Randanini cemeteries and a few may still be seen in the Vigna Randanini catacomb courtyard. Finds of terra-cotta coffins cited by Rutgers in non-Jewish tombs show that this form of burial was an option shared by many people in Late Antiquity.[64]

Of the clay coffins found in the Monteverde catacomb, approximately twenty rested upon the soil or on other coffins of the same material or on masonry sarcophagi, even in one case on a chest-shaped sepulcher.[65] The discovery was surprising to Muller not only for the number of coffins but also for their disposition and usage at an apparently late date, possibly the late fourth to early fifth century CE, but terra-cotta sarcophagi are now known to have been used at that time.[66]

"Sarcofagi Formati" (Makeshift Sarcophagi)

Among the Jewish catacombs of Rome, burial receptacles formed of vases or assembled from parts of vases, called "sarcofagi formati," appear to have been unique to the Monteverde site. They remained in use from the beginnings of that cemetery through a long subsequent period, and were found in many parts of the catacomb. Such sarcofagi formati, some quite large and containing the remnants of bones, were well represented in poor Christian and pagan burials, and are especially profuse in North Africa.[67]

Muller noted in the Monteverde cemetery that a split vessel could hold an adolescent body, with the crack or gap covered with earth, shreds, and stones. An adult could be placed between the upper and lower halves of a split large vase; curved fragments of similar vessels covered any openings. The mouth of the vase was sealed with lime mortar and bits of clay.[68] Vases were used not only for primary inhumation burials, but also as cinerary urns and ossuaries.

At times, in both Christian and Jewish burials, quicklime was placed with the bodies or spread in the folds of the sheet in which the deceased was wrapped, to expedite the process of excarnation and possibly bone-collection (see the section on Ossilegium, below). Used in the "sarcofagi formati" in order to hasten decomposition, the lime made these coffins literally sarcophagi, "flesh devourers." In the Monteverde cemetery, Muller discovered a number of broken pieces of "sarcofagi formati" encrusted with lime, and some still-visible residue suggests that lime also was scattered inside the cavities of loculi in this site, as well as others in Rome.

In a gallery of the Monteverde catacomb, several bodies were found that had been placed "directly on the soil". The Jews believed that the redemptive powers of the earth on the decaying body, especially the earth of Palestine. This belief could account for the frequency of Jewish burials without coffins, and, perhaps, for such burials among many ancient cultures for millennia.[69] When receptacles were used, the bottom of the receptacle was often perforated to permit the return of the remains to the earth. Rabbi Judah Ha-Nasi stipulated that holes be bored in the bottom of his coffin so that his body might be in contact with the holy soil. An aspect of this belief finds biblical expression, for example, in Ecclesiastes 12:7: "Then shall the dust return to the earth as it was, and the spirit shall return unto God who gave it."

Ossilegium and Bone-Collecting

In the practice of secondary burial (ossilegium), the newly-deceased would be interred or laid upon a bier for the period of time necessary to insure that the bones would have become bare. After the appropriate period, with faith in the promise that the Lord would cause the "dry bones" to rise up and live again, the bones of the deceased would be gathered up from the original grave and placed in an ossuary chest or a larger tomb with those of family members or others.[70]

Large collections of bones, especially of the deceased from the Diaspora brought back to lie with their fathers in Israel, were found in pits, kokhim, trough-graves, and other receptacles at Beth She'arim. In Jerusalem, also, ossuaries of the Second Temple period were found containing the bodies of several individuals.[71]

Through the millennia, bones have occupied varying degrees of importance in burial rites. For many of the ancients, the essence of a being resided in the bones, and the tradition of excarnation had precedents as far back as eight thousand years ago during the Neolithic period. In Anatolia, in the eastern Mediterranean area, excarnation was accomplished by allowing vultures to strip the bones.[72]

In Palestine, ossilegium, the collecting of bones for secondary burial in special receptacles, dates to the fourth millennium BCE. The ossuaries of that period (often made of clay) might resemble houses, sheep, dogs, or fantastic animals. Some were decorated with horns, palmettes, palm branches, animals, birds, and men, representations that recurred over four thousand years later in the paintings and reliefs in the catacombs of Rome.

From Hellenistic times on, the Jews of Palestine had used loculi or kokhim for bone-collecting, often storing the ossuary chests directly in the shaft. In Rome, however, no evidence to date has suggested that the kokhim in the Vigna Randanini catacombs had ever been used for anything other than primary inhumation.[73]

In Palestine, around the mid-first century BCE, and for a century thereafter, ossuary chests were used for ossilegium, their form perhaps reflecting influences from lands further East, such as Persia, where bones were collected in embellished, chest-like ossuaries (astodans). For the ancient Jews, the destruction of the flesh implied the expiation of sins, and the enduring bones reflected the hope of resurrection. Consistent with the Pharisaic belief in the importance of intact bones for achieving the anticipated resurrection, we read in Psalm 34:20, "He keepeth all his bones; not one of them is broken".[74] The tradition was evoked in John 19:36 where, after the crucifixion of Jesus, he writes, "The scripture should be fulfilled, a bone of him shall not be broken." Much earlier, in Ezekiel's vision, the presence of bones was essential for the resurrection of Israel: "Thus saith the Lord God unto these ones (of the exiles in Israel): Behold, I will cause breath to enter into you, and you shall live.”[75]

Practically speaking, bone collecting gave a small number of Jews the opportunity to have their remains transported to Palestine in adherence to the tradition of being "gathered unto" their people and sleeping with their fathers, as at Beth She'arim and in early burials.[76]

[1] Pozzolana, abundant in thick strata around Rome, Naples, and various parts of Italy, played a crucial role in Roman architecture. When combined with lime, it served as a primary component of the renowned Roman mortar, forming the basis for the city's remarkable architectural innovations and achievements: B. Fletcher, A History of Architecture on the Comparative Method, revised by R. A. Cordingley (New York: Scribner's, 1961), p. 168. The substantial quarrying of pozzolana in the vicinity of some catacombs contributed to the collapse of their regions. Additionally, water conduits were integrated into certain cemeteries; for example, a channel was identified in the upper Torlonia catacomb by Fasola: U. M. Fasola, "Le due catacombe di Villa Torlonia," in Rivista di Archeologia Cristiana 52 (1976), pp. 32-35, fig. 14; pp. 43 and 48.

[2] For example, Fasola proposed in "Torlonia", pp. 44-45, that the development of the Torlonia burial grounds might have primarily occurred towards the east and south due to property constraints in the north and west.

[3] N. Muller, "Il cimitero degli ebrei posto sulla via Portuense," in Rendiconti della Pontificia Accademia Romana di Archeologia 2.12 (1915), p. 226.

[4] R. Garrucci, "Cimitero degli antichi ebrei scoperto recentimente in Vigna Randanini," in Dissertazioni archeologiche di vario argomento 2 (1865), p. 178.

[5] Muller, "Il cimitero," p. 220.

[6] Muller, "Le catacombe degli Ebrei presso la via Appia Pignatelli," in Mitteilungen des Archäologischen Instituts," Roman section vol. 1 (1886), pp. 49, 51.

[7] Fasola, "Torlonia," p. 33. The principal north to south gallery of Domitilla which is "the longest of Roma sotterranea," measures 206 meters in length: P. Testini, Archeologia cristiana, 2d. ed. (Bari: Edipuglia, 1980), p. 101, fig. 21.

[8] U. M. Fasola, "Les catacombes entre la legende et l' histoire," in Les dossiers de l'archeologie 18 (1976), p. 57.

[9] O. Marucchi, Le catacombe romane (Rome: Desclée-Lefevre, 1903), pp. 508-509, 512; Muller, "Il cimitero," p. 225; P. Testini, Le catacombe e gli antichi cimiteri cristiani in Roma (Bologna, Cappelli 1966), p. 74; J. P. Kirsch, La catacomba di Priscilla (Rome: Societa' Amici delle Catacombe, 1969), p. 8.

[10] Peristephanon 11, p. 153, ff. (translation of J. S. Northcote and W. R. Brownlow in Roma sotterranea, or An account of the Roman catacombs, especially of the cemetery of St. Callixtus, compiled from the works of Commendatore de Rossi (London, Longmans, Green & Company, 1879), pp. 168-169).

[11] J. H. Breasted, Development of Religion and Thought in Ancient Egypt (New York: Scribner's, 1912), pp. 264-266. This ceremony was performed for the dead not only at the start of the New Year, the greatest of the Egyptian feast days, but on other feast dates as well.

[12] J. M. C. Toynbee, Death and Burial in the Roman World (London: Thames & Hudson, 1971), p. 63.

[13] F. I. Grundt, Die Trauergebrauche der Hebraer (Leipzig: Lemmel & Co., 1868), p. 19; S. Klein, Tod und Begrabnis in Palastina zur Zeit der Tannaiten (Berlin: Itzkowski, 1908), p. 32. It is still a Jewish custom to observe a seven-day mourning period. For lamps with Jewish motifs, see E. R. Goodenough, Jewish Symbols in the Greco-Roman Period, vol. 1 (New York: Pantheon, 1953), pp. 139-164 and notes. Lamps have also been found in Greek burials, being particularly prevalent at Corinth from the fourth century on: D. Kurtz and J. Boardman, Greek burial customs. Aspects of Greek and Roman life (Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 1971), p. 211.

[14] Fasola, "Torlonia," p. 59.

[15] Muller, "Il cimitero," pp. 245-246; Garrucci, Vigna Randanini, pp. 8-9; idem, Dissertazioni, p. 151. H. J. Leon noted "small niches for lamps, averaging four to six inches, cut at irregular intervals (in) the walls of the galleries and of the private chambers": Jews of Ancient Rome (Philadelphia, 1960), p. 60.

[16] Testini, Cimiteri cristiani, pp. 279-280; D. Mazzoleni, "L'arte delle catacombe," in Archeo Dossier 8 (1985), p. 20.

[17] Muller, "Il cimitero," pp. 225-226.

[18] L. V. Rutgers, The Jews in Late Ancient Rome (Leiden-Boston, Brill, 1995), pp. 58-59.

[19] Loculus ("a small place") is a diminutive of the Latin word locus ("place"); "sepolcro a fossa" is a grave in the form of a trench.

[20] Muller, "Il cimitero," pp. 224 and 227-228; two types of "sepolcri a fossa" were found in the Monteverde cemetery: the "fossa doppia", a double trench tomb, and the more numerous "fossa semplice", a simple trench for an individual. Testini also stated that the oblong niche was characteristic of the earlier burial regions: Testini, Archeologia cristiana, p. 99.

[21] Muller, "Il cimitero," p. 225.

[22] Children's burials in separate groups also have been noted in necropolises of the Archaic and Classical periods in Greece: see D. Kurtz and J. Boardman, Greek Burial Customs (London, 1971), pp. 71, 72, 190.

[23] Leon, Jews of Ancient Rome, pp. 59-60, 63, note 3.

[24] Fasola, "Torlonia," p. 52; H. W. Beyer and H. Lietzmann, Die jüdische Katakombe der Villa Torlonia in Rom (Berlin: Walter de Gruyter & Co, 1930), p. 3.

[25] N. Avigad, Beth Shearim 3: The Excavations 1953-1958 (New Brunswick: Rutgers University Press, 1976), pp. 242, 257, note 47. However, there is no prohibition in the Halakah against burying the bones of several persons together. This is seen at Beth She'arim, where large collections of bones were found in pits, kokhim, trough graves, and other receptacles: likewise, in Jerusalem, ossuaries could hold the bones of several individuals. In Rome, a Jewish "bone pit" has not been clearly identified, but individual floor trenches or formae holding more than one burial are detected in Jewish catacombs, including Monteverde: Muller, "Il cimitero," pp. 226-227, 237.

[26] Muller, "Il cimitero," pp. 226-228; Fasola, "Torlonia," p. 51, fig. 24. The "loculo ad arcosolio" was described as a little larger than average, with its roof slightly arched so that on the exterior, the slight curve of the upper edge of the opening made the tomb resemble an arcosolium with a shallow arch. It occurred most often in the lowest position in the tiers of loculi, and would hold two bodies, one above the other. A slanted partition of tiles, attached with lime mortar to each other and to the walls, was set in place above the first body to separate it from the second, which was laid on the partition. Few tiles remain in situ, but cavities in the tuff walls, into which the diagonal divider would have been fitted, show how it had been attached. The arched niches for multiple burials are described by R. Garrucci, Cimitero ebraico, pp. 7-8. They resembled the forma, the multileveled trench grave cut into the floor of a chamber or gallery.

[27] Bosio considered this type of sealing to be "peculiar to Jewish sepulchral architecture": Roma Sotterranea (Rome, 1632), p. 142; Muller, "Il cimitero," p. 229.

[28] Garrucci, Cimitero ebraico, pp. 8, 11; Fasola, "Torlonia," pp. 39-40.

[29] For Southern Italy: Muller, RM I, p. 51; In a brief excavation of 1885 of a burial hypogeum near the via Appia Pignatelli, nearly opposite one of the entrances into the Vigna Randanini site, Muller found the same types of tomb closures, which led him to consider this cemetery also Jewish. In the absence of other signs of Judaism, however, the Appia Pignatelli site today is termed "private" or "anonymous" by D. Noy, Jewish Inscriptions of Western Europe 2 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1995), p. 181 and by Rutgers, Jews of Late Ancient Rome, p. 33.

[30] Fasola, "Torlonia," pp. 39-40.

[31] Garrucci, Cimitero ebraico, p. 12; H. Leclercq, Manuel d'archéologie chrétienne depuis les origines jusqu'au VIIIe siècle, 1 (Paris: Letouzey et Ane, 1907), p. 501.

[32] Garrucci, Dissertazioni, p. 171.

[33] As found in Rome, Venosa, Sicily, Beth She'arim and other sites. In Beth She'arim, the trough graves were often cut perpendicularly to the arcosolium for access to each burial. If needed, a trough grave parallel to the arcosolium wall could be fitted in behind them: Avigad, Beth She'arim 3, p. 259, ff.

[34] Although sometimes the ceiling of an arcosolium might be flattened, especially in older regions of the underground burial sites, and termed a "mensa" tomb, it was more common for the ceiling to be curved.

[35] Fasola, "Torlonia", pp. 38-39.

[36] Garrucci, Cimitero ebraico, p. 8; A. Konikoff, Sarcophagi from the Jewish Catacombs of Ancient Rome. A Catalogue Raisonné (Stuttgart: Franz Steiner Verlag, 1986), p. 20.

[37] Marrucchi, Catacombe romane, p. 513, inscription 56 (CIJ 1.612); Jewish Inscriptions of Western Europe 1, pp. 76-78.

[38] Kurtz and Boardman, Greek Burial Customs, pp. 302-305.

[39] Leon's measurements of the Vigna Randanini kokhim indicate that the kokhim in Rome might have been slightly larger on average than those in the East: Leon, Jews of Ancient Rome, p. 60, note 2.

[40] Such concerns might be reflected in precautions regarding the closing of the eyes of the deceased: to do so was an immediate priority after death but one would be said to be "guilty of death" if the eyes were closed before the actual moment of death: Klein, Tod und Begrabnis in Palastina, pp. 21, 35-36; A. P. Bender, "Beliefs, Rites, and Customs of the Jews, Connected with Death, Burial, and Mourning," in Jewish Quarterly Review 7:4-5 (1895), pp. 101-103.

[41] Such adaptations of kokhim burials were also present in older cemeteries such as that of the Villa Pamphilii, where there were pagan and possibly Christian burials: Testini, Cimiteri cristiani, p. 106, and fig. 29; Testini, Archeologia Cristiana, p. 97 and fig. 18.

[42] Rutgers, Jews in Late Ancient Rome, pp. 61-62.

[43] Garrucci, Cimitero ebraico, p. 65.

[44] Garrucci, Dissertazioni, p. 171.

[45] Marucchi, Catacombe romane, p. 245.

[46] Garrucci, Cimitero Ebraico, p. 8.

[47] G. B. de Rossi, Bullettino di Archeologia Cristiana 3:5, pp. 38-39.

[48] Garrucci, Cimitero ebraico, pp. 8, 11-13; Dissertazioni, pp. 170-171. The use of tiles as lids for cists or sarcophagi goes back to the Bronze Age, but, beginning in the Late Archaic period in Greece, they were used to make the entire grave. The covering tiles leaning toward each other to form a gable recalled a house-like structure; Kurtz and Boardman, Greek Burial Customs, pp. 191-192. Graves in a floor, sealed with inscribed slabs, could foreshadow the later tombs of notable persons buried in the pavements of churches.

[49] The underground multi-leveled formae appear to have been anticipated by Classical and Hellenistic multi-storied tile graves at such sites as Locri in southern Italy: Kurtz and Boardman, Greek Burial Customs, pp. 312-313.

[50] Muller, Il cimitero, p. 230; I. E. S. Edwards, The Pyramids of Egypt (Harmondsworth: Pelican Books, 1961), pp. 39-40; W. B. Emery, Archaic Egypt (Harmondsworth: Penguin Books, 1961), pp. 47, 54.

[51] Muller, Il cimitero, pp. 229-231; D. Harden, The Phoenicians (London: Thames and Hudson. 1962), p. 106; Kurtz and Boardman, Greek Burial Customs, pp. 81-82, 106, 283-286.

[52] R. Paribeni, "Catacomba giudaica sulla via Nomentana," in Notizie degli scavi di antichità (1920), p. 143; Beyer and Lietzmann, Die jüdische Katakombe der Villa Torlonia in Rom, p. 1.

[53] Muller, "Il cimitero," pp. 232-233.

[54] Muller, "Il cimitero," pp. 229-231.

[55] Fasola, "Torlonia", pp. 38-39.

[56] Fasola, "Torlonia," p. 38.

[57] Marucchi, Catacombe romane, pp. 512-513 (now the via Casilina).

[58] Muller, "Il cimitero," p. 238. Such "tombe a cassone" (tombs in the form of a chest) have been found in pagan burial grounds such as those at the Isola Sacra in Fiumicino and above the Domitilla cemetery: see Ferrua, Domitilla, pp. 180, 185.

[59] Fasola, "Torlonia," pp. 38-39.

[60] S. Marianatos, Crete and Mycenae (London: Thames and Hudson, 1960), p. 152, pls. 126-127; Kurtz and Boardman, Greek Burial Customs, p. 72. The long history of clay coffins goes back at least to Early Dynastic Ur in the third millennium BCE: L. Wooley, Excavations at Ur: A Record of Twelve Years' Work (New York: Thomas Y. Crowell, 1965), pp. 54, 75. At Beth She'arim, the clay coffins found were mostly fragmentary: N. Avigad, Beth Shearim 3, pp. 182-183, 223, note 165. These were apparently produced in Phoenicia, and were found with objects dated from the second through fourth centuries CE.

[61] 2 Samuel 3:31.

[62] Mark 15:46.

[63] Genesis 50:26.

[64] N. Avigad, Beth Shearim 3, pp. 136-183.

[65] Rutgers, Jews in Late Ancient Rome, p. 59.

[66] Muller, "Il cimitero," pp. 232-233.

[67] Muller, "Il cimitero," p. 241; Klein, p. 99.

[68] A large piece of a child's skull encased in a mass of lime was found in a piece of a terra-cotta container in the Monteverde catacomb.

[69] Muller, "Il cimitero," p. 237.

[70] Predynastic Egyptians were buried directly in the earth. A similar motive may have pertained to the burials of the Late Bronze Age in the Aegean world, with the deceased interred in bathtub or chest-like clay larnakes with holes drilled into the bottom: E. Vermeule, Greece in the Bronze Age (Chicago and London: University of Chicago Press), 1964, pp. 210-211. Such perforations are apparent in the bottom of the Hagia Triada stone sarcophagus: C. Long, "Ayia Triadha Sarcophagus," in SIMA 41 (1973), p. 16.

[71] For example, B. Mazar, Beth She'arim 1: Report on the Excavations During 1936-1940 (New Brunswick, N.J.: Rutgers University Press, 1973), p. 56, and Avigad, Beth She'arim 3, pp. 114-115.

[72] For an ossuary in situ in the arcosolium of a family tomb in Jerusalem, see G. Avni and Z. Greenhut, "Akeldama," in Biblical Archaeology Review 20.6 (Nov./Dec. 1994), p. 42.

[73] E. Vermeule, Aspects of Death in Early Greek Art and Poetry (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1979), pp. 46-47, fig. 5.

[74] L. Y. Rahmani, "Jewish Rock-Cut Tombs in Jerusalem," in 'Atiqot 3 (1961), pp. 117-118. The Pharisees were members of a Jewish sect with strict traditional religious beliefs as opposed to the Sadducees, the more affluent, aristocratic, and priestly sect, who were more influenced by Hellenism.

[75] Ezekiel 37:5.

[76] Genesis 49:29, 33; 2 Chronicles 32:33.