Flora: Motifs and Symbolism. Excerpt from: Estelle Shohet Brettman, Vaults of Memory: The Roman Jewish Catacombs and their Context in the Ancient Mediterranean World, with Amy K. Hirschfeld, Florence Wolsky, & Jessica Dello Russo. Boston: International Catacomb Society, 1991-2017 (rev. 2024).

"To everything there is a season, and a time to every purpose under the heaven: A time to be born, and a time to die; a time to plant and a time to pluck up that which is planted” (Eccl. 3:1-2). Ancient peoples were deeply aware of natural phenomena and their parallels in the stages of birth, maturation, decline, and death in their own life cycles.

In ancient art and literature as in the imagery of the catacombs, death and rebirth are allegorized as the seasonal cycles of vegetation - a constant theme which pervades this publication. In the language of the Bible, humankind is often metaphorized as plant life. In her prophesied restoration, Israel is compared to a plant: “He [The Lord] shall cause them that come of Jacob to take root: Israel shall blossom and bud and fill the face of the world with fruit" (Is. 27:3, 6).

On a less benign note, the ungodly will be punished like suffering plants: "...neither shall his substance continue, neither shall he prolong the perfection thereof upon the earth...the flame shall dry up his branches...and his branch shall not be green" (Job 15:29-30, 32-33). Also, "And now also the axe is laid unto the root of the trees: every tree therefore which bringeth not forth good fruit is hewn down and cast into the fire" (Luke 3:7-9; Matt. 3:7-10).[1]

The Lord also offers his bounty for the cycle of the seasons: "And it shall come to pass, if ye (Israel) shall hearken diligently unto my commandments...That I [the Lord] will give you the rain of your land in his due season, the first rain and the latter rain, that thou mayest gather in thy corn, and thy wine, and thy oil" (Deut. 11:13-14).

In Ugaritic myth, the destruction of Mot and his planting leads to the resurrection of Baal (storm god of vegetation) and the renewal of vegetation.[2] In another account of the Creation of Man, man is pictured as sprouting from the soil "like grain from the ground."[3]

The concept of the deceased sprouting grain appears to be illustrated on an Early Bronze Age (ca. 2700 B.C.E.) stone stele from Arad on which a figure lying within a frame with arms raised is incised with wheat growing from the shoulders instead of a head. A similar figure stands above or behind this figuration--the scene perhaps alluding to the annual rising or rebirth of the Near Eastern vegetation god, Dumuzi (or Tammuz). Spikes of wheat have been depicted sprouting from heads of figures with raised arms as early as the Predynastic period Egypt.[4]

Fig. 1. Representation of the mummy Osiris "covered with earth and sand" in which "barley" was "sown." The effigy lies on a frame covered with a reed mat and a cloth. Upon germination the "verdant carpet" would assume the "form of Osiris." From the tomb of Mai-her-peri (or Maaperi), Valley of the Kings, Thebes.[5] This ritual, in which the grain would be watered for a week, was conducted in the autumnal period of the New Year and related to the renewal of nature and the revivification of the deceased in some form, such as in the expressions "I germinate like the plants,"[6] and "Except a corn of wheat fall into the ground and die, it abideth alone: but if it die, it bringeth forth much fruit" (John 12:24).

Cultivation of grain, metaphor for the cycle of death and resurrection, was central to the Greek cult of Demeter practiced in the Eleusinian mysteries. The resurrection of the god Osiris, who also represented the fertilizing inundation of the Nile, was associated with the germination of wheat and thus the grain when seeded in the ground was a metaphor for the dead Osiris, a vegetation god whose grave must be watered like the dry land. When it sprouted, it symbolized his rebirth and thus by analogy that of the interred. An incantation is pronounced during the second hour in embalming ceremony during which water is poured out every hour: "O Osiris... take to thee this thy cool water, which is in this land, which begets all living things which this land gives... Thou partakest thereof, thou livest thereon... thou breathest the air that is in it. It hath begotten thee, and thou comest forth living...".[7]

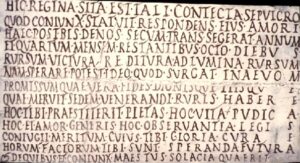

Fig. 2. In the inscription of Regina, the reference to "ascent to light" is not unlike the planting of seeds in the Greek mystery religions and the rising toward the light and sun, often depicted in Greek art as a reemergence from the earth. Thus, the disintegration of the seed gives rise to new birth and growth. From the Catacomb of Monteverde, now in the Vatican Museums.

Thus, in Near Eastern traditions, the New Year festival, often celebrated the appearance of divinity or the manifestations thereof such as rain and sun or depicted rebirth of ancient fertility gods. This period frequently became the occasion for the renewal of royal power and reaffirmation of the king as surrogate and executor of divine will, who would perpetuate the original order of creation, triumphing over Chaos, and thereby assure the cyclical renewal of nature. As for example, the Sumerian kingship which descended from heaven with the performance of the New Year rites; and at the time of the Jewish New Year, the Lord would appear as earthly ruler on "the day of the Lord", when "the Lord shall be king over all the earth," "whoso will not come up... unto Jerusalem to worship the King, the Lord of hosts," "and to keep the feast of tabernacles... even upon them there shall be no rain" (Zech. 14:1, 9, 16, 17).[8]

New Year's festivals were associated with the end of and anticipated the renewal of various growing seasons and their divine embodiments in such oriental cultures as the Mesopotamian, Canaanite, and Egyptian. In the Egyptian rituals, the Djed column (emblem of permanence and stability of nature's order) was raised symbolizing the yearly resurrection of Osiris, and his revitalization after the inundation of the Nile had reached its peak. This was also the period in which the "glorification of the blessed" or the deceased, the "earliest Feast of All-Souls," during which the living shared their offering of food and drink with the departed, was observed by Egyptians.[9] In the appointed years, the raising of the Djed column also marked the very ancient Sed festival or jubilee, the occasion for the reconfirmation and renewal of the divine powers of the pharaoh when he arrayed himself in the garb of Osiris and probably performed the role of the god of vegetation and resurrection.

When David ruled Israel, New Year's Day was observed in an agricultural festival (originally the time of an ancient nomadic celebration) immediately after the seven-day Passover festival. Taking place at that time was the investiture or re-investiture of the king, also associated with the rebirth and advent of the vegetation god along with the cutting of the new crop like its Canaanite prototype. The ceremonies reached a climax at the sanctuary atop the Mount of Olives, the abode of the divine king or god of the underworld. Following the ritual mourning period for the demise of the old vegetation cycle, the Canaanite antecedent celebrated the recreation of cosmic order and fertility in a feast for seven days after the dedication of the Temple.[10]

Fig. 3. The Djed column, often considered by scholars as the symbol for the backbone of Osiris and the seat of his resurrection, may have derived its origin from a sacred tree, and at its time of elevation in the autumn when the waters of the Nile were beginning to fertilize the dry earth at "the Season of Coming Forth," this ceremony signaled the raising of the god from the grave.[11]

With a rope, a priest elevates the tree-like Djed column (the symbol for the trunk of the tree which had served as the coffin of Osiris). On it is perched the falcon the symbol of Horus, incarnated in each pharaoh, appropriately, near the ankh or crux ansata, the sign for life eternal, which is thrust into the top right side of the column. The arisen Osiris stands below with his crook and flail in mummified form, a representation much like that of dead pharaohs who were identified with this god in death. Thoth, the ibis-headed god of wisdom and writing, appears to be pointing to the projecting ankh. The scribe of the gods is followed by a royal sekhem wand which would ensure continuity of power.

The jackal god of mummification, Anubis, who with the later participation of Horus was instrumental in restoring the murdered Osiris, according to the legend, completes the pageant on the right. A couchant lion, a beast often representing divinities, the power of monarchs, guardians or embodying other qualities, flanks the scene on the left. Below, Nephthys appropriately dominates the scene, her hand on the shenu, sign for eternity. Two jackals (Anubis) and amuletic eyes of Horus enclose the hieroglyphs above.[12] Drawing of the end of the carved granite sarcophagus of the Kushite king Aspelta. First half of sixth century B.C.E.[13]

Roses/Rosettes

The rose, one of the most ancient flowers, has assumed many meanings. Like the dove, it was the attribute of Aphrodite/Venus. When strewn on the chariot race-course, roses symbolized victory.

In a funerary ambiance, roses promised eternal spring, immortality, and rebirth for the ancient Greeks, and the custom lingered on for the Romans. Roses were central to the spring festival of the Rosalia, when they were strewn on the tombs and on the effigies of deceased Romans.

Representations of roses or rosettes (often a divine attribute as noted below), sometimes associated with animals such as lions, bulls, and caprids or their composites, were found in the decoration or furnishings of tombs as early as the third millennium B.C.E. Royal Cemetery of Ur. Rosettes decorated Mycenaean tombs. They appeared in Orchomenos (Boeotia) on the vault of a chamber in the thirteenth century B.C.E. tholos tomb of King Minyas; purportedly, bronze rosettes were affixed to the walls of a similar side-chamber in the so-called Treasury of Atreus, the famed monumental tomb at Mycenae.[14] The flower of Ishtar-Aphrodite-Venus was carved on tombstones in sixth century B.C.E. Athens.[15]

Not only was this flower depicted in funerary contexts but also in such environs of the world of the living, as the Dura Europos synagogue built during the first half of the third century; apparently plaster rosettes had been applied to the panel above the Ark.[16] And on a Mesopotamian cylinder seal of the early third millennium B.C.E., a stylized star-like rosette on another of the same vintage, caprids nibble on rosette-like vegetation growing from branches held by a man clad in a skirt decorated with a lozenge-shaped pattern.[17] He could be a royal priest of Inanna, Sumerian version of the Akkadian-Semitic fertility goddess Ishtar.[18]

Fig. 4. A Rosette of Eternity. "Vindicianos Mellarch(on)." From the Monteverde catacomb, now in the Vatican Museums. A compass-drawn rosette enclosed in a double circle (resembling the configuration of the star-like object on the mosaic floor of the Hammam Lif Synagogue) was carved on this finely incised marble.

The Vine

The plant most frequently seen in art and alluded to in writing was the grapevine, brought to the Greek and Roman world by Dionysos, a God associated with resurrection and eternal life. To the ancients, wine represented a regenerative force, the bounty of heaven, and a glorious gift to mankind. From Homeric times wine was poured on the remains of heroes and royalty, and grapevines were part of the funerary ritual.

For the Biblical prophet Isaiah "The vineyard of the Lord of hosts is the house of Israel, and the men of Judah his pleasant plant..." (Isa. 5:7) whom the Lord cared for and protected. And the psalmist prayed for the redemption of his people: "Return, ...O God of hosts: look down from heaven, and behold, and visit this vine; And the vineyard which thy right hand hath planted, and the branch that thou madest strong for thyself" (Ps. 80:14-15).

Just as the vineyard was equated with the "house of Israel" in Isaiah, for early Christians it signified the Church, and the laborers in the vineyard were devout Christians performing the work of the Lord.

Reflecting this image, Jesus referred to himself as the "true vine," with God as the "husbandman" (John 15:1- 2, 5). The wine of the Eucharist represented the blood of Christ, and to the apostles at the Last Supper Jesus asserted: "I am the vine, ye are the branches: He that abideth in me, and I in him, the same bringeth forth much fruit: for without me ye can do nothing" (John 15:5).

Fig. 5. Catalogue, p. 26, n. 116. A Laboring Putto. On a sarcophagus lid a putto harvests grapes from a vine beside the titulus which might have enclosed a painted epitaph or dipinto. From the catacombs of the Villa Torlonia, Rome.

And in Psalm 80:8-9, Israel is again compared to a vine: "Thou hast brought a vine out of Egypt.... Thou preparedst room before it, and didst cause it to take deep root, and it filled the land."

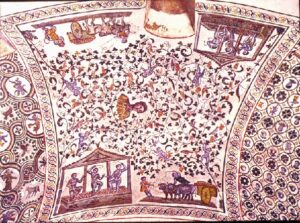

Fig. 6. Catalogue, p. 26, n. 117. Mosaic of Vintage Scenes. Doves and industrious amorini-like youths pursue their business within a heavenly bower of scrolled vine tendrils covering a section of the mosaic vault in the ambulatory of the mausoleum of Emperor Constantine's daughters. The bust in the center may be a portrait of Sta. Costanza. C. mid-4th century. Mausoleum of Sta. Costanza, Rome.

Fig. 7. Catalogue, p. 26, n. 118. Tasting the Fruits of his Efforts. Seated in a vineyard, Dionysius sips the divine ambrosia from his kantharos, while his retinue of satyrs, who metamorphose into appealing putti in Roman art, gambol to lighten their tasks. Attic black-figure amphora. C. 450 B.C.E.

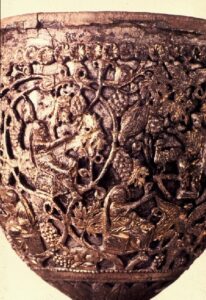

Fig. 8. Catalogue, pp. 26-27, n. 119. Antioch Chalice. Pierced silver-gilt overlays a solid silver cup, an outstanding example of the skill of the silversmith of the first half of the sixth century. Jesus, nimbed by his throne-like chair, assumes the role of philosopher- teacher. He is surrounded by doves and ten figures, probably the apostles, also in high-backed seats. They appear to be engaged in discourse under the shade of their vine. In the "last days" or when Zion is restored, the Biblical prophet envisioned: "nation shall not lift up a sword against nation, neither shall they learn war any more. But they shall sit every man under his vine" (Micah 4:1, 3).

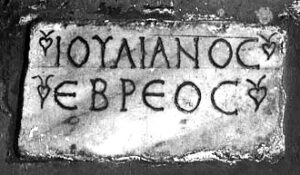

Fig. 9. Catalogue, p. 27, n. 120. Julianus, a Hebrew Perhaps the wish for a blissful afterlife is implied in the four vine leaves punctuating the beginning and ends of the two-line inscription. Catacombs of Monteverde, Rome, now in the Vatican Museums.

Fig. 10. Shalom appears again in the epitaph "Here lies Faustina." The traditional lulav, menorah, and shofar are carved amidst three theatrical masks, derived from Dionysiac imagery. A rare example of the use of Hebrew in the Jewish catacombs of Rome, now in the Terme Museum.[19]

Fig. 11. Catalogue, p. 27, n. 121. Dionysius Crosses the Sea with Cavorting Marine Companions, interior of a Greek kylix drinking cup from Vulci (Etruria), signed by the master potter Exekias in 535 B.C.E. Beset by pirates while on a voyage, Dionysos transformed them into benevolent dolphins and caused a vine to sprout on board. This scene also suggests the legend of the god bringing the vine to the west. Here are combined two major symbols of salvation, the vine and the dolphin, with the Graeco-Roman divinity whose cult promised immortality to his followers. München, Staatlichen Antikensammlungen.

Grapevines were part of the funerary ritual of Middle Bronze Age Jericho, of the Hittites, and of the Greeks appearing in their burials and/or funerary processions.[20] And so, the grape appears to have offered hope for life in the hereafter, and possibly a blessing even for this life (as in the "cup of blessing") in eastern Mediterranean beliefs.

Fig. 12. Masks of Silenus and Pan are carved above an ornate column in what might have been part of a Dionysiac scene, much favored in Roman funerary iconography. A corner fragment of the highly decorated sarcophagus from the catacombs of the Villa Torlonia, displays the vestiges of a sport (or variation?) of the standard griffin mauling the head of a ram, much favored in Roman funerary iconography.

“Tree of Life”

Fig. 13. A basket of fruit (possibly pomegranates) and roses. Detail from vault painting. Crypt of S. Gennaro, Christian catacomb of Pretestato, Rome.

Fig. 14. A basket of flowers, perhaps roses, and/or fruits. Detail from vault painting. Cubiculum II, catacomb of Vigna Randanini. In the contemporary catacombs of Beth She'arim, baskets or bowls of fruit were carved in relief.

Fig. 15. Pictorial allusions to nature's abundance are often found in pagan tombs and domiciles like the Villa Piccola, now incorporated into the S. Sebastiano catacomb well as in Christian and Jewish burials.

Like the cornucopia or horn of plenty, the basket was an ancient symbol of Nature's profusion and often suggested divine personifications of abundance. When filled with bread or fruit, baskets might have symbolized the "first fruits, harvested from earth's bounty, the sacramental redemptive offerings to the divinity (Deut. 26:2); or when filled with roses the basket could symbolize hope, perhaps of divine beneficence.[35]1 And in (the Israelite prophet Elisha's small miracle (or miracle of lesser proportions".. and brought the man of God bread of the first fruits, twenty loaves of barley, .... And his servitor said, what should I set this before a hundred men? He said again, Give the people that they may eat; for thus saith the Lord....” (2 Kings 4:42-45).

During the Exodus the starving Israelites "asked" and the Lord "brought quails and satisfied them with the bread of heaven" (Ps. 105: 39,40). "And the house of Israel called the name thereof Manna" (Exod. 16:31). "the Lord thy God"... who fed thee in the wilderness with manna...to do thee good at thy latter end;" (Deut. 8: 14,16). "Then said the Lord unto Moses, Behold I shall rain bread from heaven for you" (Exod:16:4) For the bread of God is he which cometh down from heaven and giveth life unto the world" (John 6:33).

Fig. 16. Nature's Gifts. Basket of earth's bounty. (Detail from Vault, cubiculum II, catacomb of Vigna Randanini, Rome. The basket like cornucopia was an ancient symbol of Nature's abundance often personified by gods and goddesses. Filled with bread and the fruit of the vine, they might have symbolized the first fruits, harvested from earth's bounty, the sacramental offerings to the divinity in gratitude for past performance, and with the hope of future divine beneficence. Several inscriptions from the Jewish catacombs bear incised baskets with dotted configurations which might allude to first fruits of the grain harvest. Possibly the vessels delineated on that gold glass fragment, considered by many scholars as bearing a representation of the Temple, rest on the sacred table for the divine shew bread and perhaps one of the undetermined objects in addition to the traditional cult objects represents an offering of the first fruits.

Fig. 17. Abraham's "First Fruit" On a horned altar, a ram is sacrificed as the surrogate for Isaac, Abraham's first fruit to ensure (in a divine covenant) the Lord's blessing on all the nations of the earth (Gen. 22:2-18). In much the same tradition Jesus is considered a first fruit first to arise from the dead and offered for salvation of the first fruits of conversion (1 Cor. 15:23) this concept, perhaps also reflected in the "blood of the grape" and the loaves in the painting. Cubiculum C, catacomb of Via Latina.

The horn or a replica offered liquid sustenance, usually wine, as a rhyton (drinking vessel, a favorite in Dionysiac scenes). Then again, it provided more solid fare as the cornucopia, attribute of such fertility and beneficent deities as Tellus, Abbondanza, Fortuna (often syncretized with Tyche and sometimes displaying characteristics of Aphrodite-Venus) and Isis, who like Hathor, the Egyptian cow-goddess with whom she was later merged (or conflated?), on occasion, bore horns on her head, as did other Oriental goddesses, perhaps as early as the late fourth millennium in Sumerian iconography.[36] Possibly, the Cretan divinities to whom the shrines with horns of consecration were dedicated and who, in turn, assimilated these horns in the form of crowns of horns, were fertility deities, also associated with tombs.

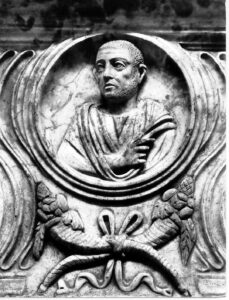

Fig. 18. Divine Beneficence (or Horns of Plenty and the like). A wreathlike clypeus encircles the ravaged portrait togate bust appearing to rise from a base consisting of a vase supported by two cornucopias bound together by a bow. These horns of plenty abound with fruit, possibly pomegranates and pine cones. Fragment of a strigulated marble sarcophagus from the catacombs of Vigna Randanini, Rome.[37]

The pine cone is associated with such vegetation gods as Attis and Dionysius and their fertility rites which celebrated seasonal death and rebirth. A popular or favored Old Testament theme of salvation in early Christian funerary iconographies. (redundant?) The cornucopia also indicated apotheosis during the Roman Imperial period, and the motif could have been passed into Jewish and Christian iconography with that symbolic value also. The two grandsons of Tiberius, who died very young, were depicted posthumously emerging from cornucopias on coins.[38]

Fig. 19. A similar motif, in good condition, is featured on the long side of a mid-third century marble strigulated sarcophagus from the catacomb of Domitilla, Rome.

Fig. 20. On the reverse of a gold 261 B.C.E. octadrachm of Arsinoe II of Egypt, is stamped the device of double cornucopias overflowing with grapes and possibly filled with bread and a pomegranate.[39] The horns of plenty may be tied with a fillet or royal diadem suggesting the prosperity of Egypt during this Ptolemaic reign.[40]

Fig. 21. "Heraldic" horns of plenty, each tied with a fillet, frame a pomegranate, all appropriate themes which were intended to suggest, for political reasons, the prosperity bestowed by the divinity who favored the rule of the Hasmonean "Yehohanan, the High Priest and the Council of the Jews." Bronze prutot. (Struck possibly by John Hyrcanus II (63-47 B.C.E.).[41]

Fig. 22. Nature's Gifts. On the left side of a tabula or panel for an inscription, lolling Genii of the Seasons flank a brimming basket of fruit, resembling pomegranates, on a pedestal; the partially chlamys-garbed putti cradle amply filled cornucopias in their left arms while with their right hands they steady smaller baskets, resembling the Greek kalathi on their right thighs. Vestiges of a similar scene on the right side of the panel are visible. Left fragment of a marble sarcophagus lid from the catacomb of Monteverde, Rome.

Fig. 23. A more modestly clad Season stands holding a pedum or crook in his right hand and a basket presumably of fruit (although resembling loaves of bread) in his left on the reverse of corner fragment.Originally this could have been part of a sarcophagus depicting the Seasons. From the Vigna Randanini catacomb. Like the cornucopia or horn of plenty, the basket was an ancient symbol of Nature's profusion seen frequently in Greek and Roman as well as Near Eastern contexts, and often suggesting divine personifications of abundance.

When filled with bread, baskets could have symbolized the "first fruits" harvested from earth's bounty, the sacramental redemptive offerings to divinity (Deut. 26:2);" or when filled with roses, the basket could signify hope perhaps of divine beneficence. And thus, in the imagery of the catacombs, baskets of earth's bounty give comfort to the departed.

Fig. 24. A sheaf of wheat and roses sprout from a basket of fruit (perhaps pomegranates) and roses. Detail of vault painting. Crypt of S. Gennaro, Christian catacomb of Pretestato, Rome.

Fig. 25. A similar spray of roses and wheat bursts forth from two baskets filled with the same (species?) to meet at the top of the painted vault of the right arcosolium of cubiculum 0. New catacomb of the Via Latina, Rome.

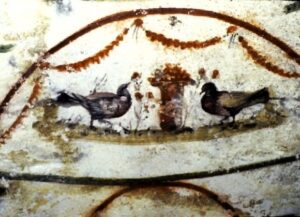

Fig. 26. Baskets of roses are accompanied by two doves framed by swags of roses in a paradisiacal setting. Perhaps much as the eucharistic offerings, and the baskets of bread and grapes might be related to such rites. opposite lunettes. Detail of vault painting. Cubiculum I, catacomb of Vigna Randanini, Rome.

Fig. 27. One of four baskets of fruit or possibly flowers such as roses. Detail of vault painting. Cubiculum II, catacomb of Vigna Randanini. A comparable basket is painted in the S. Sebastiano catacomb. Bowls of fruit were carved in relief or scratched in catacomb 1 at Beth She'arim.[42] In the catacombs at Gammarth in Tunisia, baskets probably for the vintage may have been represented.[43]

Fig. 28. A basket of fruits (apparently including pomegranates-see Pls.) is painted in a Cretan funerary ritual scene. Section of a long side of a limestone sarcophagus. Circa 1400 B.C.E. Ayia Triada, Crete.

Fig. 29. Offerings of food, including grapes, bread, and apparently a pomegranate, are made by the late fourteenth-early thirteenth century B.C.E. Egyptian King "Sethos I-Osiris" to his mother Isis so that he may be endowed with life.[44] Painted wall relief. Chapel of Isis, temple of King Sethos I at Abydos, Egypt.

Fig. 30. Two incised baskets containing dotted configurations, perhaps alluding to first fruits of the grain harvest or fruit, flank the epitaph dedicated by Sirica to her well-deserving daughter Aster (or Esther). A leaf with a particularly exaggerated stem, may be an attempt to represent an ethrog according to Goodenough.[45] Vigna Randanini catacomb. There are two other tombstones from the Jewish catacombs of Rome bearing such baskets: one, an opisthograph, also from the Vigna Randanini catacomb, dedicated to a gerousiarch and his wife by their son, an archon, and inscribed with a menorah, palm branch or lulav, bird and basket of "first fruits”;[46] the other, originally from the Monteverde catacomb and set up by a wife to her husband, was depicts the basket with dots in the right upper corner and an ethrog in the other.[47]

First fruits, of the harvest (as well as animals) were offered to the Hittite Weather-god[48] as well as to other Near Eastern divinities, perhaps to Isis particularly, those of the grain harvest, and possibly to Greek deities.[49] As for the Mesopotamians, one of the earliest depictions of such a religious festival occurs in the relief of the pageant on the late fourth millennium alabaster vase from the E-anna temple precinct (dedicated to the Sumerian fertility goddess Inanna) in Uruk (Erech).[50]

Fig. 31. Manna from Heaven and “First Fruits”. Baskets of earth's bounty, rendered in the sketchy tachiste style, give comfort to the departed. A seven-branched palm tree between two baskets of Bikkurim, the "first fruits." Obverse. An ethrog flanked by two lulavs is the device on the reverse. The coin was minted in the year "four" of the war against Rome according to the "Paleo-Hebrew" inscription on the reverse, and the epigraphy on the obverse translates as "For the redemption of Zion." These issues like other Jewish coinage were meant to stir patriotic feelings and faith in divine assistance for victory of the Jews over the Romans by recalling Temple ritual. Bronze coin. 69 C.E.[51]

[1] See also Is. 5:1-7; Jer. 11:16-17; Matt. 7:17-20; Rom. 11:16-24; Jude 12, among others.

[2] C. Gordon, The Common Background of Greek & Hebrew Civilization (New York: W. W. Norton & Company Inc., 1965), pp. 200-205.

[3] A. Heidel, The Babylonian Genesis (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1951), p. 71.

[4] R. Amiran, Israel Exploration Journal Reader, vol. I, "A Cult Stele from Arad," (New York, 1981), pp. 385-390.

[5] This information was imparted through the kindness of Dr. Mohamed Saleh, Director of the Egyptian Museum, Cairo.

[6] E. A. Wallis Budge, The Book of the Dead, v. 2 (London, Keegan Paul, Trench, Trubner & Co., 1901), p. 123 (Chapter LXXXIII, 1.3).

[7] E. R. Goodenough, Jewish Symbols of the Greco Roman Period (New York: Pantheon, 1956), p. 195 and A.M. Blackman, "Sacramental Ideas and Usages in Ancient Egypt," Recueil de travaux relatifs a la philologie et a l'archeologie egyptiennes et assyriennes, XXXIX (1921), p. 75.

[8] S. N. Kramer, The Sumerians (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1963), p. 328.

[9] J. Breasted, Development of Religion and Thought in Ancient Egypt (New York, Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1912), p. 264.

[10] It was during Solomon's reign that the Feast of Booths or Tabernacles, which marked the occasion of the dedication of his temple (I Kin.8) (in the seventh month, Ethanim or Tishri the equivalent of September-October) became connected with the autumnal New Year's festival according to the Tyrian solar calendar--thus returning the chronology of the Feast to the time of its earliest celebration. The Feast itself lasted seven days--it was augmented by two days for special ceremonies.)

[11] The capitals of the non-bearing pillars attached to each side of the entrance hall of Beth She'arim Catacomb 22 resemble the Djed columns and could well have been constructed for symbolic significance: N. Avigad, Beth She`arim: Report on the Excavations During 1953-1958. Vol. 3, Catacombs 12-13 (New Brunswick, New Jersey: Rutgers University Press, 1976), pp.119, 121-122.

[12] The eye of Horus when given to the dead Osiris enabled him to become a soul. Curiously, in the Mishna (Shah. 23.5), it was considered a crime of shedding blood to close the eyes of a dying person, while the soul is departing, thus suggesting that the eye is a vehicle for the transmission of the soul.

[13] Dows Dunham, The Royal Cemeteries of Kush, vol. II (Boston, 1955), fig. 64.

[14] E. Vermeule, Greece in the Bronze Age (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1964), pp.121-122.

[15] D. Kurtz and J. Boardman, Greek Burial Customs (Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 1971), p.126.

[16] C. H. Kraeling, The Excavations at Dura-Europos, Final Report VIII, Part I, The Synagogue (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1956), p.63.

[17] E. Porada, Corpus of Ancient Near Eastern Seals in North American Collections: Vol. I: The Collection of the Pierpont Morgan Library (New York: Pantheon, 1948), Fig.49.

[18] E. Strommenger, 5000 Years of the Art of Mesopotamia (London: Thames & Hudson, 1964).

[19] Since this broken lid of a sarcophagus was found outside the Porta Appia, many scholars have opined that Faustina was interred in the catacombs of Vigna Randanini; but given the date of its find, 1732, and the fact that there is a Hebrew word inscribed on it, Leon concluded that the original provenance could have been the Monteverde cemetery: H. J. Leon, Jews of Ancient Rome (Philadelphia: Jewish Publication Society of America, 1960), p.306.

[20] See E. Vermeule, Aspects of Death in Early Greek Art and Poetry (Berkeley, CA: University of California Press, 1979), p.225, n. 27.

[21] See also Is.5:1-7; Jer. 11:16-17; Matt. 7:17-20; Rom. 11:16-24; Jude 12, among others.

[22] C. Gordon, The Common Background of Greek & Hebrew Civilization, pp. 200-205.

[23] A. Heidel, Babylonian Genesis, p. 71

[24] Amiran, "A Cult Stele from Arad," pp. 385-390.

[25] This information was imparted through the kindness of Dr. Mohamed Saleh, Director of the Egyptian Museum, Cairo.

[26] E. A. Wallis Budge, Osiris and the Egyptian Resurrection, vol. 2 (London: P. L. Warner, 1911), p.123 from The Book of the Dead, Chapter LXXXIII, 1. 3.

[27] E. R. Goodenough, Jewish Symbols of the Greco Roman Period (New York: Pantheon, 1956), p. 195, and A.M. Blackman, "Sacramental Ideas and Usages in Ancient Egypt," Recueil de travaux relatifs a la philologie et a l'archeologie egyptiennes et assyriennes, XXXIX (1921), p. 75.

[28] Kramer, Sumerians, p. 328.

[29] J. Breasted, Development, p. 264.

[30] It was during Solomon's reign that the Feast of Booths or Tabernacles, which marked the occasion of the dedication of his temple (I Kin. 8) (in the seventh month, Ethanim or Tishri the equivalent of September-October) became connected with the autumnal New Year's festival according to the Tyrian solar calendar--thus returning the chronology of the Feast to the time of its earliest celebration. The Feast itself lasted seven days--it was augmented by two days for special ceremonies.

[31] The symbol for the trunk of the tree which had served as the coffin of Osiris.

[32] The eye of Horus when given to the dead Osiris enabled him to become a soul. Curiously, in the Mishna (Shah. 23.5), it was considered a crime of shedding blood to close the eyes of a dying person, while the soul is departing, thus suggesting that the eye is a vehicle for the transmission of the soul.

[33] Dows Dunham, The Royal Cemeteries of Kush, vol. II (Boston: Museum of Fine Arts, 1955), Fig. 64.

[34] 15 The capitals of the non-bearing pillars attached to each side of the entrance hall of Beth She'arim catacomb 22 resemble the Djed columns and could well have been constructed for symbolic significance. N. Avigad, Beth She`arim: Report on the Excavations During 1953-1958. Vol. 3, Catacombs 12-13 (New Brunswick, New Jersey: Rutgers University Press, 1976), pp.119, 121-122.

[35] Several inscriptions from the Jewish catacombs bear incised baskets with dotted configurations which might allude to first fruits of the grain harvest. The baskets inlaid in mosaic in the floor of the Hammam Lif Synagogue may contain loaves of bread and fruit.

[36] E. Strommenger and M. Hirmer, 5000 Years of the Art of Mesopotamia (London: Thames and Hudson, 1964), p. 384.

[37] Although Goodenough feels that, as with most sarcophagus fragments it could be intrusive, he considers it "probably Jewish": Goodenough, Jewish Symbols in the Greco-Roman Period, v. 2, pp. 29-30. Leon is not totally convinced that it is of "Jewish origin": Jews of Ancient Rome, pp. 213-214. Perhaps this relief was reused, and the unacceptable portion, the actual portrait (see below), was deliberately effaced in ancient times. But, obviously the cornucopia was not foreign to Jewish usage during this period.

[38] Goodenough, Jewish Symbols, v. 8, p. 111.

[39] C. Vermeule III, Greek, Etruscan and Roman Art (Boston: Museum of Fine Arts, 1963), p. 171.

[40] G. K. Jenkins, Ancient Greek Coins (New York, Putnam, 1972), p. 239.

[41] Y. Meshorer, Ancient Jewish Coinage Volume I: Persian Period Through Hasmonaeans (Dix Hills, NY: Amphora Books, 1982), pp. 67-68, Goodenough, Jewish Symbols, v. 8, pp. 110-111.

[42] B. Mazar, Beth She'arim v. 1 (New Brunswick, N.J.: Rutgers University Press, 1973), pp. 119, 120, 130, and possibly Pl. XXXIII; three, according to Goodenough, Jewish Symbols, v. 1, p. 97, and v. 3, fig. 82. (Mazar opts for a human head.)

[43] Goodenough, Jewish Symbols, v. 5, p. 77.

[44] During this period the blessed soul of the deceased often called his "Osiris." E. Panofsky, Tomb Sculpture (New York: H. N. Abrams, 1964), p. 14. Quote from K. Lange and M. Hirmer, Egypt: Architecture, Sculpture, Painting in Three Thousand Years (Greenwich, CT: New York Graphic Society, 1961), p. 487.

[45] Goodenough, Jewish Symbols, v. 5, p. 77.

[46] As described by J-B. Frey, Corpus Inscriptionum Judaicarum, n. 95. The extant fragment showing only the menorah and the palm branch is illustrated in Frey, p. 594.

[47] Illustrated in Frey, n. 299.

[48] O. R. Gurney, The Hittites (Harmondsworth: Penguin, 1969), p. 150.

[49] E. A. Wallis Budge, Osiris and the Egyptian Resurrection, vol.1 (London: P. L. Warner, 1911), pp. 9-10.

[50] Strommenger and Hirmer, Pl.

[51] Meshorer, Ancient Jewish Coinage v. 11, pp. 114-123, 259, and 262.