“New Light on Women's Roles in the Ancient Synagogues of the Roman Empire”

Lecture by Marisa de Spagnolis, Director of the Office of Excavations of Nocera and Sarno, Italy

Inaugural Lecture of the International Catacomb Society's Commemorative Founders' Lecture Series in Memory of Dr. Mark D. Altschule, Lt. Gen. James M. Gavin, Louise LaGorce Hickey, and Robert M. Morrison, Esq. (Co-sponsored by Hebrew College)

Delivered at Hebrew College in Brookline on April 25, 1990. An edited version of the lecture is below.

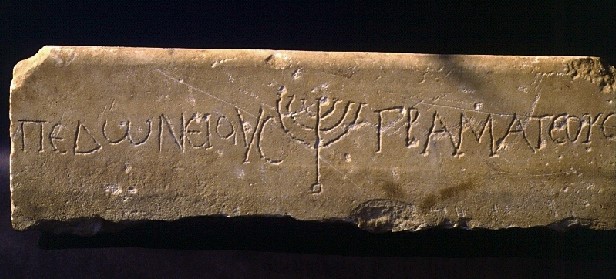

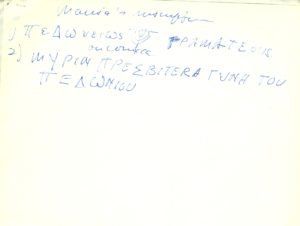

De Spagnolis' transcription of the Greek inscriptions (ICS archives).

Presentation of de Spangolis by ICS executive director, Estelle S. Brettman:

"In September 1988, during work undertaken to construct a second track of the Naples-Salerno railroad in Upper Nocera, an ancient structure was discovered.

In accordance with standard Italian policy, the Archaeology Superintendent of Salerno, Benevento, and Avellino called upon the eminent archaeologist Dr. Marisa de' Spagnolis Conticello, Director of the Office of Excavations of the surrounding area of Campania. She uncovered part of a Late Roman necropolis. Especially exciting for us is that Dr. de' Spagnolis Conticello is the wife of Dr Baldassare Conticello, Archaeological Superintendent of Pompeii and the International Catacomb Society's own Vice-President of European affairs. What a small world!"

Tomb n. 17 of this necropolis (a chest type, a cassa), presented a new feature, the presence of two marble slabs inserted into the walls of the tomb, evidently transferred from another site. Each slab bears and incised menorah along with a Greek inscription. The first inscription makes reference to a woman named Myrina, designated as a presbytera. The other mentions a man, named Pedoneius, designated as a grammateus. Described, without a doubt, are a husband and wife, one a grammateus and the other a presbytera.

The office of grammateus corresponds to the Secretary of a Council, in our case, perhaps of the Jewish community of the place, while the title of presbytera may be a personal honorific title.

Indeed, referring to a husband and wife, it the title of the woman derived from the office of her husband, he would be titled presbyter on the stone and not grammateus. Thus, in our case, the presbytera is Myrina herself. Here, possibly for the first time, we have mention of a woman official of a Jewish community in the time of the Late Roman Empire.

If the title merely reflected the position of the husband in the community, as several historians have claimed, the husband would have functioned as a presbyter. In other instances when the deceased is a woman, described a a presbytera, the interpretation has been that the woman was either the wife of a presbyter or an elderly woman. But, since in this inscription, the husband's office is mentioned, and the stone appears to be descriptive, naming two different officials.

De' Spagnolis Conticello's impressive find offers strong evidence for women holding offices in the Jewish congregations of the Late Roman Empire. This is indeed a timely revelation for contemporary women's studies, and we are most pleased that Dr. de' Spagnolis Conticello was able to make use of material from the International Catacomb Society in arriving at her conclusions.

This discovery is of major importance also because it gives evidence that there was one or more synagogues in the well-organized and rather complex community of Nocera Superiore. The presence of Jews in Antiquity was not previously known in this site.

It is most appropriate that the International Catacomb Society has invited Dr. de' Spagnolis Conticello to give the inaugural lecture of our series to be initiated in memory of those totally dedicated founders of our society: Mark D. Altschule M.D., Louise LaGorce Hickey, and Robert Morrison, Esq., all "of blessed memory".

Introduction by Marisa de' Spagnolis Conticello:

Ladies and Gentlemen:

I am very happy to be here tonight, and to have the chance to talk to you about my new discoveries in Southern Campania, in the area of Nocera.

I want to thank very much the International Catacomb Society and Hebrew College for the opportunity to come here and meet you.

My special thanks to Mrs. Estelle Brettman, Executive Director of the International Catacomb Society, who suggested that I present the Inaugural Lecture of the Commemorative Founders' Lecture Series in memory of Dr. Mark D. Altschule, MD, Lt. General James M. Gavin, Mrs. Louise LaGorce Hickey, and Robert M. Morison, Esq.

This lecture is going to be published very soon in an article in Italian.(1)

"In September of 1988 at Nocera Superiore, during the construction of a new section of railway line called Monte al Vesuvio, there came to light numerous archaeological finds from different periods. The railway descends from the northern side, touching the northwestern wall of the ancient city of Nuceria Alfaterna, and then runs eastwards, continuing and doubling the old section of railway.

Before proceeding to examine in detail the Jewish inscriptions, it would be appropriate to give some preliminary background on the site.

The ancient city of Nocera, dating back to the sixth century BCE, and situated strategically in a key position between Pompeii and Salerno, was noted in ancient writings for its political and economic importance. Various archaeological discoveries and rich necropolises also attest to the wealth of this city.

Virtually the entire settlement is still buried 3-7 meters underground. Visible today are sections of the belt of walls with towers, a small part of the city with houses and shops along one of the main streets, the remains of a Roman theater (as large as the one in Naples), and the vestiges of a baptistery dating back to the 5th century CE.

During the work on the construction of the railway, numerous archaeological finds came to light. I shall present at this time only a small selection.

One is a tomb of the 5th century BCE with a few objects, among which is a splendid red-figured kylix with a representation of an athlete.

Another tomb, of the 5th century BCE, has rich funerary furnishings, among which are two black-figured lekythoi and an oinochoe with black glaze.

Numerous are the finds from more recent periods, such as a tomb of the 1st century BCE of a two-year old child with toys placed nearby.

In another child's tomb of the period immediately following the eruption of Vesuvius in 79 CE was found a recycled terra-cotta slab molded with griffins of the Augustan period.

We shall now examine another very important zone discovered during the course of this archaeological work which was always done outside of the eastern wall of the ancient city. Here we excavated 70 superimposed stipi (a kind of well) with votive offerings, including thousands of miniature terra-cotta vases and lamp, pertaining to a syncretistic goddess who combined attributes of such Oriental deities as Isis and Cybele. These stipi date from the third century BCE to the second century CE, the latter excavated in a 50 cm. deep layer of volcanic lapilli from the 79 CE Vesuvian eruption. The presence of a sanctuary dedicated to Oriental religions suggests the existence of a large population of Oriental people here.

In the course of building a parapet of the new section of the Monte al Vesuvio railway in the San Clemente locality (in the Santa Lucia trench at the mouth of the Alfaterna tunnel, along the second line) there came to light a series of tombs from the first century CE (graves nn. 3, 4, 5, 7, 10), and from the Late Imperial Period, the latter nine in number (nn. 9, 11-21). For its duration, the excavation was in the constant control of and carried out always in the presence of technical personnel from the Archaeological Superintendence of Salerno, Benevento and Avellino, all under my direction and responsibility.

This Late Roman necropolis has been explored only within the limits of the new railway section and it has been ascertained that it is clearly located south-southwest of this site, in part under modern buildings. The tombs were uncovered easily because they were situated at a shallow depth of 30 cm. above a layer of soft stone dating back to 79 CE, and only two were dug deeper by cutting through the layer of soft stone. Tombs nn. 13 and 16 presented the traditional gable-type form, with twin large tiles covering the length plus two at the head; tombs nn. 15, 16, 18, and 19 were of the coffin type, formed by blocks of tuff with tile coverings, and still another type (nn. 20 and 21) was the normal trench grave, with the body deposited either directly in the earth or upon a layer of tiles (n. 14); also, in this case, with a covering of tiles. All the tombs presented the same orientation - southeast-northwest, with the head towards the northwest. No traces of funerary furnishings were found.

On September 23, 1988, tomb n. 17 of the coffin type, formed by irregular tuff blocks, squared on the interior and covered by three large, flat tiles, was excavated. Two tiles were placed transversely with an east-west orientation, and a third in a longitudinal direction southwest-northeast. Even the supine position of the deceased was supported by tiles. This coffin-type grave formed by blocks of bluish-gray nucerine tuff presented a new element, not found in the other tombs explored to date in the dig: three blocks of recycled marble, two of which had been inserted into the base of the long southwest side and the third in the long northwest side (we do not at present have more information on the chemical composition of the marble or probably site of quarrying).

Upon dismantling the tomb, I was able to observe that one of the two marble blocks placed along the southwest side and facing inward towards the burial was inscribed with Greek characters and a representation of the menorah, the heptalycnos (7-branched) candelabrum of the Jews: the other block on this side was anepigraphic, or without epigraphy. The marble block found in the northeast side also revealed an inscription in Greek characters and a second representation of a Jewish candelabrum in seven-branched form. All three blocks were of Italic marble, and were made as parts of architectural elements, particularly frames, each with the mounting between them completely different. The dimensions and with of the slabs varied: 1. length 70 cm, height 15 cm; 2. length 80 cm, height 24 cm; 3. length 1 m., 5 cm., height 12 cm. The three marble blocks were place in the tomb in the same manner as the blocks of tuff and clearly appear to have been recycled since they were originally part of a building which had been destroyed.

The first block bears a Greek inscription on one line with characters irregularly distributed. Of differing height varying from 4 to 7 cm, the letters read (in English transliteration) PEDONEIOUS GRAMATEOUS. In considering the fracture of the marble after the second word (marble which on the reverse side exhibits rough indentations for attachment to a walled structure), it is possible to hypothesize that the inscription continued. The marble is inscribed with the name Pedoneious and the title Gramateous. A representation of a menorah divides the two words. Since the second block is not of particular interest, and without inscribed characters, I shall not discuss it further here. The third marble block, discovered on the northeast side of the tomb, is also inscribed in Greek letters of varying height (between 4 to 7 cm.) in a single irregular line incised on a triangular section of cornice. It reads (again, in English transcription) MYRINA PRESBYTERA GYNE TOU PEDONIU. The reverse side of the stone is drilled with three holes for the insertion of iron bars and, like the other inscribed marble, there are rough indentations for affixing it to a walled structure on this side.(2)

The first block bears a Greek inscription on one line with characters irregularly distributed. Of differing height varying from 4 to 7 cm, the letters read (in English transliteration) PEDONEIOUS GRAMATEOUS. In considering the fracture of the marble after the second word (marble which on the reverse side exhibits rough indentations for attachment to a walled structure), it is possible to hypothesize that the inscription continued. The marble is inscribed with the name Pedoneious and the title Gramateous. A representation of a menorah divides the two words. Since the second block is not of particular interest, and without inscribed characters, I shall not discuss it further here. The third marble block, discovered on the northeast side of the tomb, is also inscribed in Greek letters of varying height (between 4 to 7 cm.) in a single irregular line incised on a triangular section of cornice. It reads (again, in English transcription) MYRINA PRESBYTERA GYNE TOU PEDONIU. The reverse side of the stone is drilled with three holes for the insertion of iron bars and, like the other inscribed marble, there are rough indentations for affixing it to a walled structure on this side.(2)

This second inscription is also incomplete, and runs along an irregular line with characters of different height, with the paleography distinguished by apexed lunate characters, as, for example, in the letters epsilon, sigma, and omega: apparently, the transcriber - perhaps a Jew - could not distinguish the diphthong oi from the simple u. This inscription bears the name of Myrina Presbytera, wife of Pedoneios, the person in the preceding epigraph. The two epigraphs refer to two personages, Pedoneious and Myrina, whose names are not known from other documentation of Jews. Both emphasize the titles which follow their names. As for Myrina's title, that of presbytera, it should be noted that it is fairly rare and reserved for women, as in three of the inscriptions at Venosa, and one each in Crete, Thrace, Tripolitania, and Rome. The male version, "presbyter" is more frequently noted. Since few examples of titles recorded for women in a Jewish or Christian context are known to date, this has led scholars to offer various hypotheses, some of which we shall summarize here. In the Corpus Inscriptionum Judaicarum, Fr. Jean-Baptiste Frey quotes Samuel Krauss who states that the title presbytera was probably given to women who were wives of presbyters and thus the title was but a reflection of the status of the husband. Frey also records Jean Juster's presumption that presbytera was "a simple title", conferred by custom upon women "pieuse et venerees dans la communite'". On his part, Frey translates the term simply as a "femme âgée". In a study on the Jews of Ancient Rome published some decades later, in 1960, Harry J. Leon opines that this title may be a transfer to the wife of the husband's title as an honorific, or an honor conferred on those women who had distinguished themselves with special merit within the community or, in some cases, signifying their great age. As in the case for men, this title seems to be related to a venerated social status.

This second inscription is also incomplete, and runs along an irregular line with characters of different height, with the paleography distinguished by apexed lunate characters, as, for example, in the letters epsilon, sigma, and omega: apparently, the transcriber - perhaps a Jew - could not distinguish the diphthong oi from the simple u. This inscription bears the name of Myrina Presbytera, wife of Pedoneios, the person in the preceding epigraph. The two epigraphs refer to two personages, Pedoneious and Myrina, whose names are not known from other documentation of Jews. Both emphasize the titles which follow their names. As for Myrina's title, that of presbytera, it should be noted that it is fairly rare and reserved for women, as in three of the inscriptions at Venosa, and one each in Crete, Thrace, Tripolitania, and Rome. The male version, "presbyter" is more frequently noted. Since few examples of titles recorded for women in a Jewish or Christian context are known to date, this has led scholars to offer various hypotheses, some of which we shall summarize here. In the Corpus Inscriptionum Judaicarum, Fr. Jean-Baptiste Frey quotes Samuel Krauss who states that the title presbytera was probably given to women who were wives of presbyters and thus the title was but a reflection of the status of the husband. Frey also records Jean Juster's presumption that presbytera was "a simple title", conferred by custom upon women "pieuse et venerees dans la communite'". On his part, Frey translates the term simply as a "femme âgée". In a study on the Jews of Ancient Rome published some decades later, in 1960, Harry J. Leon opines that this title may be a transfer to the wife of the husband's title as an honorific, or an honor conferred on those women who had distinguished themselves with special merit within the community or, in some cases, signifying their great age. As in the case for men, this title seems to be related to a venerated social status.

Examining the office of Pedoneious, gramateous or grammateus, we must remember that it is extensively recorded and appears in some form, in fact, twenty-eight times in Jewish epitaphs from Rome. For grammateus there also exists various hypotheses in the literature, since, again, scholars do not agree on the exact significance of the title.

Emil Schürer states that the grammateus was not a proper official of the community, but instead was a doctor of the Jewish Law or expert in judicial procedures. Abraham Berliner also believes that the grammatei are individuals especially learned in the Law or scribes in the common sense of the term. Hermann Vogelstein and Paul Rieger believe that this title was given to men who were experts in copying the scrolls of the Law used in the synagogues or in producing and revising, according to prescription, contracts, marriage certificates, and divorce documents. On the other hand, Frey deduces from examining numerous epitaphs that grammateus does not mean scribe but rather a highly-esteemed functionary. Leon claims that the grammateus was the secretary of the congregation who recorded the minutes of the congregational gerusia and those of the members' assembly, updated lists of the community members, and conserved important documents just as an appointed individual does in a similar role in the synagogue today. Both scholars agree that because of the importance of his office, this official had the right to inscribe it on his tombstone.

The discovery of the two inscriptions, re-utilized as burial material in a tomb belonging to a subsequent period, permits us to acquire data of notable interest.

These unexpected finds were the first evidence in the city of Nuceria of the presence of a Jewish community - a fact never before documented (even though there was evidence of the presence of Jews in the vicinity, perhaps even in Pompeii). My findings, indeed, permit us to determine that there must have been a Jewish community in this city large enough and important enough to be organized in its civil functions. These two inscriptions bearing the two titles associated with the administration of the community, in just two lines and seven words of text in total, offer evidence of a Jewish community at Nuceria. That this community was organized in its administrative functions, as the titles of grammateous and presbytera would suggest, implies the existence of Jewish communal life and of a synagogue around which a community gathered. Further confirmation of this hypothesis is offered by the inscriptions themselves, written in Greek, the language most commonly used in inscriptions identified as Jewish in the area of the Roman Diaspora. Typical of dedicatory epigraphy, they were written on a single line, only, upon architectural slabs - not in common epitaph style, written out on multiple lines. As for the use of architectural elements employed for the inscriptions, it is still to be determined whether these elements were utilized casually or if they were chosen deliberately as architectural elements of a building. Myrina's inscription was originally the entablature of a door. This suggests that we are dealing with marbles removed from a synagogue. In a particular type of synagogue - that called "Galilean" - there are many dedicatory inscriptions on supports of architectural elements, on doorways, on columns, on frames, and on other slabs associated with these structures.

The building to which our inscriptions had been affixed was destroyed by the time the Late Antique or early Medieval necropolis that we are exploring came into use, and these inscriptions were re-employed in a tomb. Also very noteworthy in these two Jewish inscriptions is the rarity that in just seven words total on two lines of text, as mentioned above, there are two titles and they are attributed to a married couple: a Presbytera, wife of a Grammateous. These two inscriptions, in fact, could help resolve the much-debated problem we have discussed, namely, the significance of the attribution of the two titles. To have derived the term presbytera from the title grammateus is improbable. Therefore, the title attributed to Myrina has to be considered her own and not reflective. The question is whether her title signifies a religious office within the community, as I personally believe, or was just an honorific title without administrative significance. This cannot be proven with certainty, but a step forward seems to have been made in clarifying the confusion surrounding women bearing official titles in ancient synagogues. As for Pedoneious, he clearly would have had important administrative responsibilities within the Jewish community, as described above.

These two inscriptions in Greek together with those in storage in the National Archaeological Museum in Naples are the only Jewish inscriptions from the Roman era discovered in Campania that are written in the Greek language. It must be observed, however, that the Jewish inscriptions written in Greek found in and around Naples are of a funerary nature, whereas our two from Nocera appear almost certainly to be of a dedicatory character. Because of the similarity in the paleography of the cited inscriptions, we can arrive at a chronology of the fourth or fifth centuries CE.

This data seem to confirm Leon's observation that inscriptions recording Jewish presbyteri outside of the city of Rome date to around the fourth century CE and later. Our two inscriptions were evidently incised by two different persons (lapicidi), as shown by the diversity of the execution of the letters in each inscription. It can be noted, for example, that the tops of the letters in one of the inscriptions are missing in the other, and that the menorah is depicted differently on each slab. In spite of the paleographic differences between the two stones, the dates of execution must have been fairly close, of course, because they belonged to a husband and wife.

The discovery of the two inscriptions in the territory of Nocera is of major interest because it opens a new page in the history of Nuceria Alfaterna, a city which is relatively unknown. We hope that future surveys and scientific investigation into its territory, together with systematic excavations and explorations, will lead to new and significant finds relative to the discovery of a Jewish presence in the area. Such finds would augment even further the information from this fortunate initial discovery revealing a hitherto unknown Jewish congregation.

The existence of this Jewish community at Nocera should not come as a complete surprise because there is now much evidence for a Jewish presence in Campania. From literary and archaeological sources, we gather that Jewish lived in Pozzuoli, Nola, Bacoli, Marano, Brusciano, Capua, Naples, and, not far from our territory, at Herculaneum, Pompeii, Stabiae, and Salerno. Recently, there was discovered at Cimitile, near Nola, a terra-cotta lamp with a relief representing the menorah. The presence of Jewish communities in the area of southern Campania dates from the first century CE to modern times, but none of this evidence attests directly or indirectly to the existence in the Roman period of organized communities with their own autonomous cult buildings.

Adding to these testimonies of great significance is my discovery of the two Jewish inscriptions in Greek, which were brought to light during our excavations in the necropolis of S. Clemente in Nocera. Referring as they do to the administrative organization of the Jewish community, they testify to the presence of Jews in ancient Nuceria during the fourth century CE, and the likelihood that these Jews had at least one synagogue building for assembling.

In Italy to date (1990), only two synagogue structures have been discovered: one in Ostia near Rome and another in Bovillae Marina in Calabria. The discovery of our inscriptions reveals the existence of a third synagogue in the vicinity of Nocera. I feel that this synagogue was not too distant from the sanctuary dedicated to the Oriental cults found on the east side of the town, outside of the city belt walls. We hope that further excavations in the area will offer us the possibility of discovering this synagogue.

- Marisa de' Spagnolis Conticello (2 May1989); edited and annotated by Jessica Dello Russo (2018)

(1) Conticello De' Spagnolis, M., Una testimonianza ebraica a Nuceria Alfaterna, in Ercolano 1738-1988. 250 anni di ricerca archeologica. Atti del Convegno Internazionale (Ravello-Ercolano-Napoli-Pompei, 30 ottobre -5 novembre 1988), a cura di F. Dell'Orto, Roma 1993: 243-252.

(2) The inscriptions were subsequently published in AE 1994, 401 a-b and SEG 44 (1994), 818.

Additional bibliography at: http://www.marisadespagnolis.it/; DeSpagnolisText

Italian summary (2 May 1989) of Conticello's lecture "Iscrizioni Ebraiche da Nocera Superiore (Salerno)"

Nel settembre 1988, conducendosi lavori per la costruzione di un secondo tratto della ferrovia statale Napoli-Salerno, in Nocera Superiore, venivano in luce strutture antiche.

Per conto della Soprintendenza Archeologica per le Provincie di Salerno, Benevento ed Avellino, interveniva la dott.ssa Maria de' Spagnolis Conticello, direttore dell'Ufficio Scavi dell' agro Nocerino-Sarnese, che metteva in luce una parte di una grande necropoli tardo-romana.

La tomba n. 17 di detta necropoli, del tipo a cassa, ha presentato, come elemento di novita', la presenza di due lastre marmoree inserite nelle pareti della tomba, evidentemente elementi di risulta, trasferiti da altro sito, che recavano incise ciascuna un'iscrizione in lingua greca e ciascuna un candelabro ebraico eptalynchne (Menorah).

La prima delle due iscrizioni fa diretto riferimento ad una donna, di nome Myrina, definita come presbytera.

La seconda iscrizione fa diretto riferimento ad un uomo, di nome Pedoneius, definito come grammateus.

Si tratta, senza alcun dubbio, di una coppia di marito e moglie, l'uno grammateus e l'altra presbytera.

La carica di grammateus potrebbe corrispondere a quella di segretario di un consiglio, nel nostro caso forse della communita' ebraica del luogo, mentre la carica di presbytera non puo' che essere una carica onorifica personale.

Infatti, trattandosi di marito e moglie ed essendo la donna presbytera, se il titolo le derivasse dalla carica del marito, questi sarebbe definito nell'iscrizione presbyter e non grammateus. Quindi, nel nostro caso, presbytera e' la stessa Myrina. Con il che' si verebbe a dimostrare, forse per la prima volta, che, all'interno della communita' ebraica di epoca tardo romana, le donne avevano esse stesse accesso alle cariche pubbliche, almeno all'interno della communita' stessa.

Si trattava, allora, per la communita' di Nocera Superiore, di una communita' organizzata e piuttosto complessa, talche' si deve ritenere che vi fossero una o piu' sinagoghe operanti. Un tale circostanza, come anche la stessa presenza di ebrei a Nocera Superiore, non e' finora mai stata attestata, per cui la scoperta e' dalle massima importanza

Le due iscrizioni sono state pubblicamente presentate, alla presenza di rappresentanti della communita' ebraica di Napoli, al Convegno per il 250 anniversario dei primi scavi in territorio vesuviano, ad ottobre 1988 a Pompei, e saranno pubblicate negli Atti del Convegno, in corso di stampa.

To the Editor of the Jewish Advocate:

"I am delighted that Judith S. Antonelli's excellent May 3, 1990 Advocate coverage of the International Catacomb Society's Inaugural Lecture for its Commemorative Founders'' Lecture Series, given at Hebrew College by Dr. Marisa de Spagnolis Conticello, Director of the Excavations Office at Nocera-Sarno in Italy, sparked the interest of an indomitable Ellen Feingold to visit Norcera Superiore in the region of Campania, Southern Italy - the site for Dr. de Spagnolis Conticello's significant find. Indeed, such persistence in the face of seemingly insurmountable challenges is often rewarded in Italy by unexpected bonuses, and the enthusiastic cooperation and response of the Italians who are so pleased when stranieri or foreigners manifest interest in and knowledge of their historical and cultural treasures. Going to extreme lengths to resolve any language barriers, the Italians will assist in any way possible. Their precipitous mountain roads are so well-constructed that the adventurous, off-the-beaten path traveller is usually rewarded with insights into comparatively tranquil small-town life and the nostalgic, pastoral, harvesting and fishing scenes as of yore, far from the frenetic pace of heavily-frequented tourist haunts. I have been fortunate in experiencing this serendipity for many years, either during the course of my own investigations or in conducting tours.

Perhaps Ms. Feingold and her readers would be interested in knowing that the two Jewish inscriptions from Dr. De Spangolis Conticello's excavation point to a date of the fourth to fifth centuries CE for the synagogue and congregation supported by this hitherto unknown organized Jewish community in ancient Norcera. Also, to emend her chronology further, the visible remains of the fourth-century synagogue at Ancient Ostia, near the airport of Rome, which may have undergone even earlier stages of remodeling, rest on the vestiges of a first-century building, perhaps the earliest synagogue in Europe known to date. Another major revelation, inferred by the Norcera inscriptions, brings more corroborative evidence to the the notion that women could have held religious offices within some Jewish congregations of the Roman Empire. As Ms. Feingold concludes, we can only hope that such valuable sites which illuminate our past will continue to be explored and preserved. The mission of the International Catacomb Society is to assist in this endeavor by creating an awareness of the existence of these sites and their importance."

- Estelle S. Brettman, Executive Director, International Catacomb Society