Roaming through Sicily to explore off-the-beaten path archaeological zones, I stumbled upon and dislodged a large rock in an early Christian-to-Byzantine period cemetery. On the underside of that rock, I saw a crude graffito of a menorah. It was as if Zeus had hurled one of his fabled thunderbolts in the rugged, culturally diverse hinterlands of Sicily. My first instinct, in this land so fraught with history and mythology, was to carry the astounding "find" with me in order to protect it for posterity. Hardly a practical plan for such a heavy rock--so, reluctantly, I left it behind.

On a return visit two years later to check on the protection of this treasure, I was assured by a custodian that the Soprintendente was aware of its existence and that it would be properly safeguarded. I had explored catacombs in Rome and Israel, but this marked the first time I had perceived a Jewish symbol in such an unlikely place. I wondered how many artifacts bearing Jewish symbols remained undiscovered in early Christian cemeteries.

The Sicilian revelation was the spark that fired the subterranean odyssey—travels that were to transport me from the orderly row houses of Boston's staid Beacon Hill to the cavernous, tortuous passages of the Roman catacombs. This fateful incident would change the meaning and direction of my life.

Later, after pursuing my studies, I would contrast my reactions to those of Antonio Bosio, the "Columbus of Roma Sotterranea," in 1602 when he perceived a menorah in a hitherto unknown setting, a Jewish catacomb. Bosio disclaimed the possibility of the burial of heretic or pagan sects near Christian burials and emphasized its separateness by isolating his record of it in a separate chapter in his posthumously published book, Roma Sotterranea (1632-34). I, however, was fascinated by the chance detection of a menorah in an early Christian cemetery. The possibilities that it suggested, either of neighboring Jewish and Christian burials or the continued use of sacred Jewish symbols by Christians, were intriguing.

The dimensions of my insights broadened within a month's time when my husband and I set off to realize his lifetime ambition of sailing down the Nile on a felluca (Egyptian sailboat). My previous work and studies at the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston and as a special student at Harvard University heightened my excitement over direct contact with the remarkable monuments in this ancient land. Viewing the art of Egypt strengthened my speculation that the imagery of the Roman catacombs, as well as the Graeco-Roman art that influenced it, had antecedents in the earlier art of the Mediterranean.

From these travels and earlier research was born the final statement of my future research and exhibitions. By studying parallels to the funerary art of the Roman Empire, the inference can be made that ritual art draws upon the artistic language of its period and then adapts this vocabulary to its own needs and precepts. The basic symbols persist in one form or another through the ages, as do humanity's primary concerns.

More remote clues to my involvement in this pursuit may lie in my genes. My grandfather, a rabbi and noted Talmudic scholar, was revered and beloved by his congregations in Lithuania and Portland, Maine, in his adopted country. He was known as the "Wise Man" of his shtetl (town) and the surrounding countryside. My father was a physician, a family doctor who counseled and comforted people of diverse ethnic, social, and economic backgrounds. Also very learned in the Talmud and the Bible, he devoted his spare time to writing a book entitled Kinships, a work based on the fundamental ties uniting all people. He saw parallels to these ties in the forces of gravity that order the relationships of planets and stars within an immense universe, a study that fascinated him. As for my peripatetic instincts, a close, adventure-loving maiden aunt from the Midwest served as a role model. Her independent, high-spirited lifestyle and search for new challenges would have excited any women's-libber, even some decades after the fact.

Ever since childhood, I have been deeply interested in mythology. In my post-college years and during work at the Museum of Fine Arts, I was intrigued by the interacting influences among ancient civilizations of the Mediterranean. My study focused on the origins of the symbols and myths used by people in an effort to understand the vicissitudes of nature and to meet the challenge of their own mortality. What better place to study the use of symbols than in the extant monuments where symbolic concepts are expressed by concrete representations! Hence, my many years of exploration of archaeological sites in and around the Mare Nostrum.

My encounters with the cemetery of Beth She'arim, replete with catacombs, in Lower Galilee in Israel, and the floor mosaics of such synagogues as those of Hamat Tiberias and Beth Alpha in the Yezreel Valley provided the earliest stimuli to the more specific study of funerary art. The Greco-Roman configurations of Medusa and the dolphin from Beth She'arim, as well as signs of the zodiac, the seasons, and Helios (the sun god) from the synagogues mentioned above were especially provocative in view of the Second Commandment's admonition against "graven images" (Exodus. 20:4).

Like many of the Jews of the Diaspora in the Graeco-Roman period, I moved on to Rome. This was a natural sequence considering that the Talmud tells us that the futures of Israel and Rome were destined to cross.

Mosaic panel in synagogue of Beth Alpha, Israel, depicting Helios-Sun at center surrounded by Zodiac symbols. DAPICS n. 0781.

The Jewish colony of Rome, whose numbers swelled to approximately 50,000 after Pompey's return from Palestine with prisoners of war, is the oldest continuous Jewish community of the Diaspora, having survived for 2,000 years. The catacombs of this city on the Tiber have yielded the largest corpus of vital information about the daily life of the Jews of ancient Rome.

My first venture into a Jewish catacomb took place in 1976. For several years I had inquired about the whereabouts and means of entering the comparatively little-known burial grounds of Torlonia. The custodian of the chief synagogue of Rome informed me that I could apply to the Pontificia Commissione di Archeologia Sacra for permission to visit a Jewish catacomb (1). I then approached Cardinal Giuseppe Caprio, at the time Monsignor Caprio, an ever-helpful friend who has always made the impossible possible. His Eminence arranged, through the kindness of Father Umberto M. Fasola, then Secretary of the Commissione, for permission and a custodian who could guide me through the Jewish catacombs under the Villa Torlonia. Because of the requirement for special permission and other protective measures, more than forty catacombs, not directly supervised by monasteries or convents, have been spared the greed and vandalism of looters and souvenir hunters.

Several weeks passed before my long-anticipated entry into the Jewish catacombs of Torlonia, northeast of the ancient walls of Rome near the intersection of the Via Lazzaro Spallanzani and the Via Nomentana. These catacombs were discovered accidentally in 1919 by laborers repairing the foundations of stables under the Villa Torlonia. Mussolini lived here from 1925 to 1944 above five acres of Jewish burials. Paradoxically, it was this dictator who once called the Jews, "strangers in Italy."

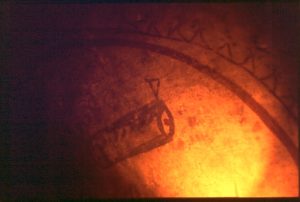

Detail of wall painting of scroll with protruding label in interior vault of arcosolium in Chamber A1, Catacombs of Villa Torlonia. Photograph taken by lamp light by Estelle S. Brettman. DAPICS n. 0717.

I had no sooner entered the dark corridors of the Torlonia catacombs when, to the total consternation of this amateur photographer, my flash refused to function. Dashed were my hopes of obtaining any visual documentation of the structure, frescoes, epigraphy, or other artifacts. Only by the careful manipulation of his trusty gas lamp did the custodian enable me to take a few slides, which were far from satisfactory in my estimation. However, since professional photographers considered them evocative of the atmosphere of the catacombs, they became part of my exhibit at the Boston Public Library four years later, in 1979-1980.

Discouraged by the failure of my photographic equipment in Torlonia, I was reluctant to prolong my frustrations and continue on my scheduled appointment for that day to explore the Christian catacomb of Domitilla. Hearing my story, a Rome shop owner, a longtime acquaintance, offered to loan me a flash attachment. With renewed expectations, I set off to keep my appointment with a fossor at Domitilla on the Via Ardeatina, southeast of the walls of Rome. Again I was to be thwarted when, during the long Roman lunch hour which includes siesta, my camera was ripped from my shoulder by the ill-famed "scippatori." These motorized handbag snatchers pounce on their unsuspecting prey at such hours when the streets of this lively city are deserted. My tearful chase through the streets of Rome after the speedily vanishing motorcycle was of no avail. After accepting a morale-boosting Cinzano, proffered by a sympathetic young couple at the inevitable local bar, I reported my loss to the police. I then climbed disconsolately onto the bus that would carry me belatedly, minus my photographic equipment, to my rendezvous.

My misadventure in Domitilla gave me insight into the difficulties experienced by earlier explorers of the catacombs. Because of the theft of my camera, I could make only cursory notes and drawings by the light of the gas lantern held by my guide. Needless to say, my illustrations were not nearly as elegant as those of the sixteenth-century investigators.

Fate was no kinder to me than to the illustrious Antonio Bosio, who had lost his way in this multilevel complex, perforated by thousands of graves. When we were ready to depart, my guide had difficulty finding the way out of this dim, humid maze in the bowels of the earth. Understandably, he was reluctant to admit that he had taken a wrong turn, a miscalculation that extended our stay by four hours. How I regretted not having marked our trail with a long thread!

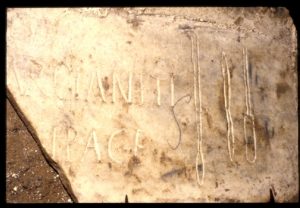

Inscription from the Catacomb of Domitilla, Rome. To the right on this fragmented inscription are three medical instruments, usually used by midwives. In Latin: " (M)arcianiti (I)n Pace", Marciana …in Peace. The tools of her calling suggest that Marciana was a midwife (obstretrix). DAPICS n. 1131.

A return trip to the Domitilla catacomb in 1980 was more productive. I had studied a drawing that documented the epitaph of one Marciana and that referred to its location in the cemetery. After consultation with Ingegnere Mario Santa Maria, Director of the Technical Office of the Pontificia Commissione di Archeologia Sacra, who supplied detailed maps, I was able to locate the inscription. It was an intriguing tombstone because next to Marciana's name were incised the tools of her trade, which suggested that she was a member of the ancient and honorable profession of midwifery. I was accompanied by Leonardo, a young Italian novice whom I had chosen as my guide because of his patience and interest in the project, in contrast to the priests in charge who frowned upon this brash American woman. After interminable climbing over difficult sections of galleries, often confronted with collapsed areas of tufa (the actual walls of the catacombs) and puddles of water, we finally arrived jubilantly at our destination. There in the glow of the candle held by Leonardo, who was, at this point, also obsessed with the search, appeared the fragmentary marble epitaph of Marciana, complete with medical instruments! It was affixed to the wall of a narrow, crumbling gallery. From that time on, the German monks who supervised this catacomb welcomed the "American archaeologist" (a new and undeserved title) with warmth.

My continuing investigations took me to other catacombs and other adventures. One such cemetery was the small, opulently decorated pagan-Christian catacomb of Via Latina. My climb down the steep, narrow stairway from the grate in the sidewalk, which was closed after our entry, evoked images of Don Juan's descent into Hell; a feeling that was reinforced when my guide, not trusting my assurances that I had special permission to photograph during my visit the catacomb, finally consented to check my statements with a telephone call. He could not have been aware that I would suffer claustrophobic anxieties brought about by his plan to leave me alone with the sidewalk grate closed forty feet above. Even the spectacular paintings, the most extensive cemeterial assemblage of biblical themes, were not enough to divert me from my fear of entrapment. Nor were my anxieties dispelled by the spectacular view of the earliest depiction of what appears to be a lesson in anatomy. Ascending together to the real world, we received no answers to our phone calls. I finally persuaded Alberto Marcocci, my guide, so admirably but exasperatingly steadfast in his loyalties to the Pontificia Commissione di Archeologia Sacra, to permit me to take photos. I promised to let him keep the rolls of film until he could verify the permission that Father Fasola had granted. The trade-off actually saved very little time, since he "generously" allowed me to take only one roll of pictures in an archive so rich in rare painted imagery that my return visit consumed at least ten rolls of film.

Detail of a wall painting of the so-called "anatomy lesson", Catacombs of via Dino Compagni, Rome. DAPICS nn. 0393, 0934.

My investigations of the Christian catacomb of SS. Pietro e Marcellino were prolonged and intensive, stretching out for hours, sometimes into the evenings, to the chagrin of the patient fossor who, like his ancient antecedents, was descended from a guild-like family of professional excavators/diggers. I actually welcomed the warm, humid atmosphere in this tufaceous womb, which proved comfort after the chill November nights in a charming but heatless attic apartment.

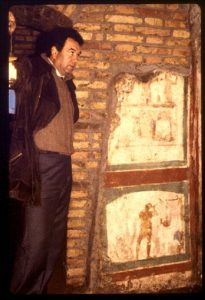

PCAS fossor Alberto Marcocci, in his "Sunday best," in the Catacombs of Pietro e Marcellino,Rome. DAPICS n. 1227.

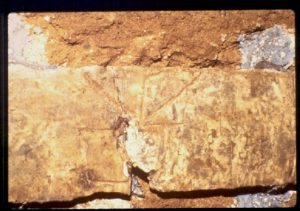

On my last Sunday in Rome, I had almost despaired of finding a Jewish symbol in this Christian catacomb. Alberto, my Diogenes, arrived nattily dressed in his Sunday best for this final expedition in the dim, narrow, slippery, winding galleries of the SS. Pietro e Marcellino catacomb. He smilingly informed me that, since he wished to enjoy part of his day of riposo, he had only a two-hour supply of fuel in his gas lamp, intimating that after that time we could lose our way in the darkness. When, undaunted, I pulled out a huge flashlight from my knapsack, the poor man shook his head in resignation, muttering, "I have never met such a persistent scholar." It all seemed worthwhile when Zeus struck again, this time with two thunderbolts, upon my perceiving two fragmented graffiti of menorahs on stone slabs in different locations of this vast necropolis. My discouraged pilot even managed to have enough time left to enjoy his Sunday dinner. Again, as in the case of the incidental menorah seen on my Sicilian adventure, perhaps such tree-like configurations could denote the adoption of a Jewish symbol of hope by Christians in the same way that Hebrew Bible imagery evolved into a didactic medium of analogies for the deliverance and redemption themes of Early Christian art.

Stem with branches on rectangular base (Chrismon?), carved on marble slab in the Catacombs of Pietro and Marcellino. DAPICS n.m 1286.

Three inscription fragments from the Catacomb of Peter and Marcellinus, Rome. The fragment at the lower left has a fragmentary depiction of foliage commonly seen as a palm branch. DAPICS n. 1280.

I returned to Roma Sotterranea a number of times to study the motifs of the catacombs. The catacomb of Vigna Randanini seemed to be the logical site from which to organize a visual essay juxtaposing the shared images in Christian and Jewish catacombs, recording Graeco-Roman and Hellenistic influences, and tracing the origins of the symbols back to the second millennium B.C.E. and even earlier. Surprisingly, the frescoes of the three highly decorated cubicula (funerary chambers) of this catacomb are Hellenistically inspired. There, very often on my back, I photographed the paintings on the typically segmented, vaulted ceilings representing the "Dome of Heaven."

Painting of a large bird - an eagle? - in a chamber in the Catacombs of San Sebastiano, Rome. DAPICS n. 0173.

A partially destroyed chamber in the catacomb of S. Sebastiano provided me with a most intriguing disclosure. While examining the vestiges of a Jonah cycle, a common biblical theme alluding to salvation in Christian iconography, I observed a striking image. A bird with a wide, powerful wingspread was apparently transporting a scarcely discernible, spindly-legged man. Father Magrini, an extremely patient and helpful member of the order of priests in charge of this cemetery, disagreed vehemently with my hypothesis that this was a representation of the Greek myth describing the abduction of Ganymede. According to the myth, the god Zeus, symbolized here by the eagle, carried the beautiful Trojan youth off to the heavens--an allegory for the spiriting away of the soul from the body. This was the only funerary painting of this motif of which I was aware. There are others carved in relief on sarcophagi and other monuments as well as in the round.

Since the figure of the man never appeared on any of my slides of this image, I eventually resigned myself to the fact that I had been hallucinating or having visions. And so, reluctantly, I put this find out of my mind. In a gratifying aftermath to this story, upon my return to the same cemetery two years later, Father Magrini greeted me with the news that my theory was correct, and that scholars of the Pontificia Commissione di Archeologia Sacra had determined that I had seen a portrayal of the Zeus-Ganymede myth. He then assisted me in positioning my camera at the proper angle so that it would record the faint image of Ganymede.

My research made me aware of the need to study and document existing material and assist in preservation procedures. Thus was planted the seed that was to germinate into the International Catacomb Society, the exhibition, Vaults of Memory: Jewish and Christian Imagery in the Catacombs of Rome, with an accompanying catalogue, and, ultimately, the comprehensive publication, Vaults of Memory, the present work.

- The catacombs of Italy were entrusted to the care of the Vatican and thus have been administered by the Pontificia Commissione di Archeologia Sacra (Pontifical Commission for Sacred Archaeology) in accordance with the 1929 Concordat between Italy and the Vatican. As part of the revision of this agreement in 1984, the Vatican ceded control over the non-Jewish catacombs to the Italian state.