Excerpt from: Estelle Shohet Brettman, Vaults of Memory: The Roman Jewish Catacombs and their Context in the Ancient Mediterranean World, with Amy K. Hirschfeld, Florence Wolsky, & Jessica Dello Russo. Boston: International Catacomb Society, 1991-2017 (rev. 2024).

Beneath the vineyards and villas in the environs of Rome lie catacombs, some discovered and then lost, some still remaining, and certainly others yet to be revealed.

Down through the centuries, the discovery of these subterranean sites has been effected through happenstance, such as laborers digging quarries or shoring up the foundations of buildings, through curiosity and interest of would-be explorers and devout Christians, or through scientific investigations by scholars and archaeologists in the course of excavation.

By and large, only the sanctuaries (and adjoining catacombs) dedicated to S. Lorenzo (catacomb of Cyriaca) on the via Tiburtina, S. Pancrazio on the via Aurelia, and S. Valentino on the via Flaminia were still visited for reasons other than vandalism and the recycling of ancient building materials. The catacombs of S. Sebastiano also in part remained accessible, but, from a confusion in topographical designation, they were commonly known as those of S. Callisto, along with other cemeteries along the Appian Way.

It was not until the 15th century that some of the catacombs in Rome were rescued from obscurity by the visits of pilgrims and reawakened humanistic interest. The pre-eminent nineteenth-century scholar of these sites, Giovanni Battista de Rossi (1822-1894), notes as an early visitor a certain Johannes Lonck (1432), who wrote is name on the walls of a cubiculum in the catacombs of Callisto. Shortly thereafter, some frates minores (friars minor, or Franciscan brothers), made several visits to this site, as did a group of Scots in 1467. Fifteenth century academicians such as members of the Accademia Romana, led by their flamboyant "pontifex maximus" (the title of a pagan priesthood later used by the Pope), Pomponius Letus, assisted by Pantagathus, sacerdos, came to the catacombs with different intentions. The Accademia Romana wished to broaden their knowledge of Classical antiquity by searching for pagan monuments, and referred to its members as unanimes antiquitatis amatores or unanimes perscrutatores antiquitatis. Pope Paul II (1464-1471) was affronted by their actions, no doubt perceiving their attitude and activities as a threat to his Christian authority.[i] The pope had good reason to suspect academy members of irreverence. The Perscrutatores, in fact, were descending like "modern pagans" into the catacombs of Callisto, Ss. Marcellino e Pietro, Pretestato, and Priscilla, where they wrote upon the ancient walls of chambers their assumed names and titles.[ii] In the end, the group was prosecuted by the local ecclesiastical authorities for amoral and heretical acts, but the publicity surrounding these accusations no doubt served to rekindle awareness of the existence of the catacombs and provoke visits by others.

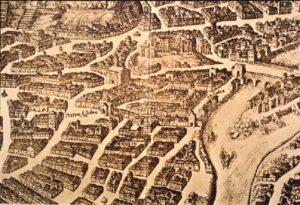

Figure 1. Rome at the time of the earliest investigators of the catacombs. Leonardo Bufalini's plan of the city of Rome in 1551 with mid-eighteenth century corrections by Giovanni Battista Nolli. From an engraving (DAPICS n. 3528).

Religiously-oriented investigation is first documented on an extensive basis by the Italian historian and antiquarian Onofrius Panvinius (1529-1568), who conducted a well-organized and methodological study of the Christian cemeteries of every region of the ancient world, but especially those of Rome, though the work was based almost entirely on mention of the sites in historical, ecclesiastical, and epigraphical sources, and not specific site knowledge. His work on the subject, De Ritu Sepeliendi Mortuos Apud Veteres Christianos Et De Eorundem Coemeteriis, printed in Cologne in the year he died (1568), and his collection of ancient epigraphs indicate that Panvinius knew of forty-three ancient cemetery locations in Rome, although he was not an active explorer of these sites and mentioned only three by name: S. Sebastiano, S. Cyriaca (S. Lorenzo) and S. Valentino. According to de Rossi, Panvinius' work was the earliest published treatise to attempt a classification of ancient Christian inscriptions. For its time, it was a "miracle of knowledge and of incredible labor," especially considering the brevity of Panvinius' own life.[iii]

Other scholars, like Antonio Agostino and Aldo Manuzio, who transcribed inscriptions seen during their visits to catacombs, took note as well of non-Christian materials such as pagan inscriptions and imperial medals, thus broadening the scope of their research.

Another dedicated student of the catacombs was Filippo Neri (1515-1595), who later became a saint and patron of Rome. This "Apostle of Rome" founded the Cenacolo Filippino in his quest to restore early Christian religious practices and trace a history of Church events. Neri spent long hours in the catacombs in spiritual meditation, a practice emulated by Carlo Borromeo (1538-1584), also canonized. Cesare Baronio (1538-1607) was appointed by Neri to continue his work. In the process of doing so, Baronio compiled extensive works on Roman martyrs and recorded the discovery of a well-preserved catacomb region decorated with paintings, today known as the "Anonymous Catacomb of via Anapo".

The date of this catacomb discovery was May 31, 1578, ten years after the printing of Panvinius' De Ritu Sepeliendi. Quarrymen working in the vineyard of one Bartolomeo Sanchez on the right hand side of the via Salaria at the second mile from Rome made a startling discovery when the tunnels they were excavating intercepted an underground burial ground in good condition. Most catacombs accessible at that time had already been despoiled of artifacts, but this site gave the public a "stupendous marvel" of the Christian underworld.

Having descended three times into this phenomenal setting, Baronio left a record of his impressions and those of other visitors.[iv] The labyrinthine construction of the catacomb and the symmetry of the chambers or cubicula seemed to strike the visitors even more than the sculpture, paintings, epigraphy, and other artifacts. An unfortunate industrial accident soon covered up the site once more, burying workers in a landslide along with access to the catacomb. To a later catacomb explorer Bosio, who tried in vain to re-enter the site, the workers had received their just rewards.[v]

The catacomb briefly opened in 1578 was incorrectly identified at the time by Baronius as that of Priscilla and as the "Ostriano cemetery" by a contemporary, the Spanish Dominican Alfonso Chacon or Ciacconio (1540-1599).[vi] When it was newly discovered in 1921 and excavated at that time by Enrico Josi, it became the "Catacomb of the Giordani" until it was finally determined to be a private cemetery.[vii] The catacomb, now named for a modern street, is strikingly decorated in parts with paintings of Biblical and New Testament scenes, conjuring up visions of a vast city buried below the suburbs of Rome, inspiring the term, “Roma Sotterranea” or Subterranean Rome, and generations of explorers.

This catacomb's loss did not deter scholars of the late sixteenth century from looking at similar sites in the suburbs of Rome. They included Ciacconio, Philip De Winghe, and De Winghe's friend and countryman, Joanne L'Heureux, nicknamed Macarius.[viii] This "noble triumvirate" documented the via Anapo catacomb and others that are known today as the cemeteries of Priscilla, Sts. Marcellinus and Peter, S. Valentino, and Callisto (coemeterium Zephyrini). L'Heureaux's study of decorated artifacts in these sites, Hagioglypta, sive picturae et sculpturae sacrae antiquiores, praesertim quae Romam reperiuntur, was not published until 1859 (in Paris, by arrangement of the Jesuit archaeologist Fr. Raffaele Garrucci). The illustrations Chacon commissioned were not very accurate, but ended up being incorporated into the published work of Antonio Bosio. The copyists Chacon employed often resorted to the artistic vernacular of their day, making for entertaining interpretations of figures and other details in catacomb art, but not always in reference to religion. Chacon's colleague, Philip De Winghe, a Flemish layman, aware of the deficiencies in his friend's work, tried to reproduce and label the material more accurately. His premature death, however, in 1592, prevented the completion of a new work on Christian monuments and his notes and other materials were not preserved in their entirety. The work of these men at the end of the sixteenth century, for all their faults and limits, along with a diary of Pomponio Ugonio describing more subterranean explorations, served as guides to those who followed in the pursuit of Christian antiquities, especially Bosio, who incorporated some of De Winghe's work into his own.

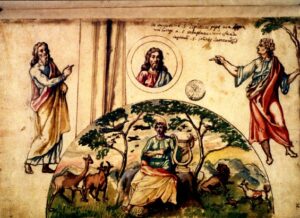

Figure 2. A Sixteenth Century View of the Paintings in the Catacombs. Cod. Vat. 5409, f. 39, Bibliotheca Apostolica Vaticana (DAPICS n. 1106).

The Spanish Dominican, Alonso Chacon (Ciacconio) documented the catacomb of Domitilla among others. His illustrator created his own version of this Domitilla fresco of Christ among the Apostles by adding the Christian symbols par excellence, the Good Shepherd and the orans, probably a representation of the praying deceased, a motif prefigured in Greco-Roman art as Pietas- a theme deriving from more ancient cultures. His illustrator recorded his own version of this fresco of Orpheus as a swinging musician seated on a boulder. The "rock" music of the Thracian bard charms the birds in the trees, the popular peacock and dove, along with such exotic beasts as a camel and a lion, in addition to the more run-of-the-mill domesticated animals. Orpheus, who figured in earlier cultures and was an antecedent to the Good Shepherd, appears to be on the verge of tapping his foot in accompaniment to the syncopated beat. Since his lower torso is almost completely destroyed in the fresco as it exists today, and the bust of Jesus on the vault of the cubiculum is now barely discernible, this early documentation is of major importance. While the artist depicted the prophet, perhaps Micah, on the left, he omitted the rock from which the water flows, on the right. Thus it was not possible to identify, as Moses, the figure on the right. In addition, the representation of Jesus, in a tondo that is actually framed concentrically by three hexagons, has been moved from the vault of the cubiculum to a central position between the two Old Testament figures. Even though the additions of the sixteenth century artist are evident and Chacon's annotations are not precise, the historical-religious value of these rare documents is undeniable. They serve as precious records (sometimes the only such) of evanescent monuments.

Figure 3. A recent view of the fresco in the lunette of the rear arcosolium in the cubiculum of Orpheus showing the variations of the copy and the destruction of the fresco (DAPICS n. 1098).

Over the next four centuries, a remarkable saga of discovery and identification of subterranean burial sites took place. For the current study, particularly relevant are the discoveries of Jewish catacombs and Jewish inscriptions.

Even before the first sighting of a Jewish catacomb was made by chance by Antonio Bosio on the southern slope of the Monteverde in 1602, specimens of Jewish epitaphs were recorded by De Winghe, Claude Menestrier, and Chacon. Almost a century later, in 1685, a doctor-scholar, Jacob Spon of Lyons, published the Miscellanea eruditae antiquitatis that included three Jewish epitaphs from ancient Rome, two of which had originally been recorded by De Winghe.

Antonio Bosio (1575-1629), by setting foot "in the shadowy city... (to embrace) a giant undertaking", was the first to describe the actual setting of an ancient Jewish cemetery.[ix] Personally familiar with many of the scholars mentioned above, including Cenacolo members Baronio and Ugonio, with whom he visited the Roman catacombs, Bosio was a law student in Rome of Maltese origin. Early on in his catacomb explorations, on 10 December 1593, he penetrated into the Catacomb of Domitilla (then confused with of Callisto). Bosio was eighteen years old at the time and risked his life trying to find a way out, coming close to "contaminating with his unclean body the sepulchers of the martyrs"[x]

This misadventure did not deter Bosio from committing himself at an early age to the study of Rome's lost subterranean cemeteries over many years. From 1593 to 1596, he explored catacombs on the via Tiburtina, via Appia, via Labicana, via Nomentana, on both via Salaria roads, the Vecchia and Nuova, the via Flaminia. He then moved on to the via Portuense, starting on the last-named ancient road in 1600. He ended up disclosing around thirty newly found burial sites. He entered them by whatever means he could, sometimes through a landslide, or a depression made by an ancient light well (lucernarium). What he could not do, except in rare instances, was excavate, which required paying workmen out of his own funds.[xi] Considering that Chacon and his colleagues had visited scarcely four or five catacombs and had seen but a small part of each one, Bosio's "great complex of discoveries" was on a truly awesome scale for his time and enabled him to amass a wealth of new information.[xii] It is true that some paintings and other artifacts that he surely saw in situ are not mentioned in his work (though we know he saw them because he left his signature on or near the find spots), leading de Rossi to question some of his idol's methods of selection. Notable instances are Bosio's omission of the famous "Mother and Child with Prophet" scene and a Good Shepherd in the Catacombs of Priscilla. But the record-keeping on the catacombs was not his alone: Bosio employed several artists to illustrate artifacts, among them Angelo Santini, who earned the nickname "Toccafondo" or "Rock-Bottom" for the breadth of his underground expeditions. The work of these artists, like that of the copyists of Chacon, was not always faithful to the style and content of the originals, but are essential documentation for many artifacts and sites.

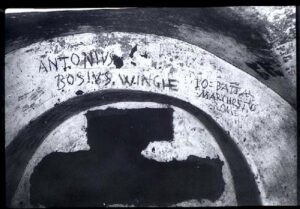

Figure 4. Two vivid reminders of Flemish Philippe de Winghe and Maltese Antonio Bosio, early sixteenth century explorers/chroniclers of the catacombs, are recorded on the face of an arcosolium in the catacomb of Priscilla. Photograph courtesy of the Pontificia Commissione di Archeologia Sacra (DAPICS n. 0480).

Figure 5. The "Columbus of Roma Sotterranea," Antionio Bosio, and his nineteenth century heir, G. B. De Rossi, left their signatures on the painted lunette of the rear arcosolium, flanked by columns. Cubiculum of the Bottai (coopers) in the Catacomb of Priscilla. Bosio's Signature (in Latin, Antonius Bosius, as signed above) is in the center, and De Rossi's, which is small and barely discernable, is on the upper right (DAPICS n. 0642).

Figure 6. A section of a plan of seventeenth century Rome showing the quarters near the Tiber which Bosio frequented in the course of his explorations. Line drawing from Giambattista Falda, La Pianta di Roma del 1676 (DAPICS n. 0911).

On December 14, 1602, Bosio, always on the hunt for cemeteries, made his way out of the Porta Portuense and climbed the Colle Rosato on the south side of the Monteverde ridge above the Tiber plain. He was accompanied by several companions, the Marquis Giovanni Pietro Caffarelli, a noble from Rome, and Giovanni Zaratino Castellini, poet and scholar. At the far end of a vineyard overlooking the Tiber River, on a property which belonged to the heirs of one Mutio Vittozzi and formerly in the possession of Bishop Ruffino, the men came across an opening that led to an underground grotto with tombs.

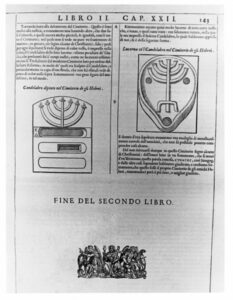

With bodies bent over to enter the narrow opening, the explorers gained access to a cemetery which was carved out of soft, often very crumbling tuff. The ruined condition of the grottoes, plus their treacherous position on a sharp declivity on the side of a rocky cliff below which extensive tuff quarries lay, put the men in danger of their safety. Almost all the passages were blocked, but Bosio and company managed to remain inside the obstructed galleries for about two hours. The tombs had little in way of decoration, but on one was the painted word fragment in Greek, "Synagog," and on many others, in fact, "almost on every tomb," the motif of the seven-branched candelabrum, the menorah of the Jews, appearing also on one of the clay lamps Bosio took away from the site. This evidence pointed to a catacomb used by Jews, not Christians. It seems to have been an unexpected find, but Bosio scrutinized it according to his usual methods, sadly concluding that "curious and greedy excavators" had looted it like all the rest. His brief mention of the site in the posthumously-published Roma Sotterranea was the first mention of a Jewish burial site in Rome in print (Bosio came across two other entrances to catacombs in the vicinity of the via Portuense, and, in 1618, penetrated into the Christian cemetery of Ponziano on the ground of the English College).[xiii]

Why had these Jewish tombs disappeared from collective memory, even, apparently, that of the Jews? Perhaps the ignorance of the existence of Jewish catacombs was of recent date, not from the time of their abandonment for burial. Even if no pilgrimages or other ritual acts had been performed since the early middle ages, the fifth century on, the Jewish catacombs might have been known to other generations. The Itinerary of a twelfth-century traveler, Benjamin of Tudela, mentions "a cave in a hill on the bank of the Tiber" where ten Jewish martyrs were buried. This suggests that the Jews in Rome at his time knew of an ancient cemetery in a location that could very well match the Monteverde site.[xiv]

Figure 7. Bosio's illustration from Roma Sotterranea,1632. The earliest methodical explorer of Roma sotterranea documented the first discovery of a Jewish catacomb, Monteverde in 1602, in this publication. Such evidence as the presence of the Greek word CYNAGOG [in Greek letters] (synagogue) and the appearance of the "candelabrum with seven lamps" "almost for every tomb" as well as on a lamp, identified this surprising find for Bosio as a Jewish catacomb, unheard of in his time (DAPICS n. 3272).

Figure 8. Engraving of a fanciful, conflated seventeenth-century conception of burials in the catacombs of Rome. Frontispiece from Roma Sotterranea. Bosio's laborious and dangerous but nonetheless methodical explorations of the catacombs of Rome were first published posthumously by Fr. Giovanni Severano in 1634 (though dated 1632) (DAPICS n. 3629).

Bosio's many catacomb discoveries earned him the unforgettable nickname from de Rossi of being the "Columbus of Roma Sotterranea," in other words, the father of new discoveries. With tremendous effort, Bosio coordinated research of Classical antiquities, Church rites, all available writings on Christian cemeteries in Rome, the acts of early Christian martyrs, and other historical documentation with his own topographical examination of catacomb sites. He eventually created a vast compilation of all these materials, providing a unique foundation and instrument of study for subsequent research. Even de Rossi, indefatigable as Bosio ever was, was stupefied by the four enormous volumes of Bosio's "ordinary leaves of paper" which he examined centuries after their compilation in the Biblioteca Vallicellina, a testament to the immense scale of Bosio's endeavor. And yet, in spite of Bosio's "marvelous persistence," he was only able to identify a small number of Christian cult sites by name. He simply did not have the archaeological data to do so which would come to light in later centuries, by means of ruthless relic extraction and more strategic digging plans. Bosio’s plan for a publication entitled the "Roma Sotterranea" included three major sections, but only the second part, that describes the actual location and contents of the catacombs, including close to 200 illustrations, was ready to print when he died in 1629. In 1634, five years after his death, the publication of Roma Sotterranea was complete, after an extensive process of editing, emending, and unfortunately also eliminating certain parts of the text by the Oratorian priest Giovanni Severano, who had been commissioned by Bosio's heirs and patrons to complete the work. Despite the delay, the work was eagerly sought after by scholars of many countries, and went through many reissues and abridgments, not to mention a Latin-language "updated" edition by another Oratorian, Paolo Aringhi, in 1661.

Over the succeeding centuries, repeated efforts were made to locate and study the Jewish catacomb Bosio had seen. Around 1740, Giuseppe Bianchini claimed to have seen the site in the company of Cardinal Domenico Passionei, and, toward the end of the eighteenth century, scholar Gaetano Migliore records that he, too, had been able to enter the site from an opening made by a rock slide but found it too structurally unstable to actually explore. He states that "as I was toiling to follow the deteriorating lines in the wall (i.e., the tomb cavities) in the dim light in the bowels of the earth, the heap of stones massed casually, the rocks, from some place or other, which were about to fall down on my head, convinced my feet to go out of doors".[xv] Migliore gives his reason for the trip as a means to ingratiate himself with local scholars (as a Neapolitan transplant to Rome) by making a plan of the site. Even in the aborted attempt, he was able to note the ruined condition of many of the tombs, the scattered fragments of epitaphs with Jewish motifs, and the aforementioned "broken down compartments for cinerary urns" (almost invariably present in Roman necropolises of long duration), decrying the shameful neglect of such antique treasures by Rome.[xvi]

Like the studies of so many of his predecessors in catacomb exploration, Migliore's work was not published during his lifetime, and the Monteverde catacomb seems to have fallen once again into oblivion, for when the Jesuit archaeologist Giuseppe Marchi made a concentrated attempt to trace its location in 1843, he came up empty. In 1892, a painter, not named in archaeologist Rodolfo Lanciani's account, searched in vain for a "subterranean palace" someone had indicated to him on the site, and "cut with his own hands a gallery 4' high by 15' long, but succeeded only in unearthing a rock-cut door without being able to determine in the end if it led to a Christian or Jewish tomb.[xvii] Not many years before, in 1879, the archaeologist Mariano Armellini had announced that the entrance to the Jewish cemetery had been found, choked by dirt. The German Lutheran scholar Nikolaus Muller, who would become the principal investigator of the site beginning in 1904, also tried several times to locate the catacomb between 1884 and 1888.[xviii] Finally, just months before the site once again came to light, French archaeologist M. Seymour de Ricci tried and failed once more to pinpoint the Jewish catacomb's location (in 1900 and 1904).

Unfortunately, the few who had succeeded since Bosio's time in accessing the Jewish catacomb of Monteverde failed to apply his careful methods of documentation, resulting in the destruction and dispersion of many of its artifacts. During this time, one of the few names that stands out for scholarship is that of Raffaele Fabretti (1618-1700), one of the appointed "Custodians of the Holy Relics and of the Cemeteries," an office created by Pope Clement X in 1672 to keep watch over the relic hunting and artifact harvesting then going on in the catacombs and other ancient Christian burial grounds. In de Rossi's estimation, Fabretti's work in epigraphy employed proto-scientific methods, the first to do so after Bosio. Two other "custodians" of the catacombs in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries were Marcantonio Boldetti and Giovanni Marangoni, witnesses to many discoveries that did not make it to print. Later scholars improved the record-keeping on this front, including Giovanni Settele (1770-1840), who tried to indicate the provenance of epitaphs being removed from the catacombs of Rome.

The first truly detailed topographical study of the Roman catacombs was finally realized thanks to Giovanni Battista de Rossi (1822-1894) and his brother Michele Stefano, respectively archaeologist and mathematician/geologist by profession. Its publication in three volumes as the Roma Sotterranea Cristiana (1864-1877) marks "the first time the principles of methodological exploration and of the study of finds in the Christian catacombs (were) documented and established".[xix] De Rossi's "General overview" (nozioni generali) is valuable to archaeologists today, particularly after his later emendations, because it reflects the mature synthesis of his research, a culmination, as it were, of many hours of analysis and investigation, begun while he was still a teen-ager.

A prolific contributor of over two hundred articles to publications, de Rossi is renowned as the father (or founder) of Christian archaeology in its modern form, just as Bosio was a stand out in a previous generation for his topographical precisions. Early on in de Rossi’s career, he worked closely with Fr. Giuseppe Marchi, SJ (1795-1860), whose study of early Christian architecture in the catacombs he continued. Marchi also encouraged de Rossi in a systematic study and catalogue of Christian epitaphs from the catacombs, a project that de Rossi envisioned would "at least partially" return "to each cemetery its inscriptions".

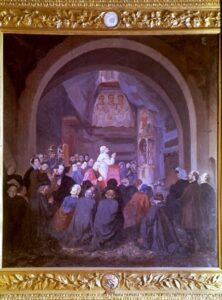

Figure 9. G. B. De Rossi (second person on the right), participates in the 1854 visit of Pope Pius IX to the catacomb of S. Callisto in celebration of the discovery of the Crypt of the Popes and the tomb of Sta. Cecilia, the scene of the festive occasion. This catacomb was rediscovered accidentally by De Rossi in 1849 (DAPICS n. 2028).

In over half a century of dedicated scholarship, de Rossi, aided by ancient documents (Classical authors as well as Church documents), medieval itineraries, papal inscriptions, pilgrims' graffiti, and his own eyewitness accounts, uncovered many monuments in the catacombs that he associated with the ancient cults of Christian martyrs. As a result of tracking down physical features alluded to in literary sources, he was able to identify several cemeteries by their ancient names. In addition, he came across nine or ten previously undocumented cemeteries. De Rossi was not deterred, like Bosio, by entrances choked with dirt, instinctively believing that monumental traces of building work in the catacombs, even if later than the era of Christian persecution, pointed to an area of particular veneration by pilgrims before the mass translations of the bodily relics of saints to churches within the walls in the Middle Ages. Any doubts harbored by de Rossi’s contemporaries as to his attributions were largely dispelled when he identified the tomb of Pope Cornelius in the catacomb region known as the "Crypt of Lucina" in 1852.[xx] This "providential" gift vindicated his topographical methods, which had consequences as well for Jewish Rome, for de Rossi’s fame won over some landowners who alerted him to new finds. In 1866, de Rossi identified a small Jewish catacomb or hypogeum below the vineyard of Count Cimarra, from which he recovered five fragmentary inscribed artifacts, including one on marble with figural representations.[xxi] He was already following the excavation of a larger Jewish site up the street in Giuseppe Randanini’s vineyard, first brought to light in 1859, and would encourage younger colleagues Orazio Marucchi and Nikolaus Muller to publish on the results of their own Jewish catacomb explorations. De Rossi's ceaseless efforts on behalf of the catacombs are best reflected in his Bullettino di Archeologia Cristiana, which documents the fruits of many years of research. He was influential enough to win the support of Pope Pius IX, who appointed him to the newly-established Commission for Sacred Archaeology in 1852, created to control exploration of the catacombs and prevent further violation of these sites.

The generation of catacomb scholars after de Rossi included Orazio Marucchi, who was able over a long career to popularize the study of these underground sites through prolific writing, as well as Mariano Armellini (1852-1896) and Henry (or Enrico) Stevenson (1854-1898). All made notable contributions to the continuation of the Roma Sotterranea Cristiana, but only Marucchi lived long enough to add new monographs to the series. In 1903, Joseph Wilpert (1857-1944), another student and successor of de Rossi, published at his own expense a comprehensive documentation of the paintings and sarcophagi of the catacombs. His work still serves as a fundamental research tool.

In the second half of the nineteenth century, in addition to investigations in the Christian cemeteries, the Commission for Sacred Archaeology also engaged in the study of newly-emerging Jewish cemetery sites in Rome. These efforts were initiated earlier by Marchi, who was eager to study the Monteverde catacomb, the only Jewish cemetery known in his time. The Jesuit’s own attempts proved to be in vain, but a second Jewish cemetery, in a completely different part of the city, along the via Appia close to the third mile marker, emerged in 1859 (or perhaps a few years earlier, in 1857).[xxii] The vineyard owner, Giuseppe Randanini, carried out excavations in the Jewish catacomb, assisted by Fr. Raffaele Garrucci, SJ (1812-1885). Before arriving in Rome, Fr. Garrucci, a Neapolitan by birth, had lived and taught in Benevento and just before his work on the Vigna Randanini site had published the manuscript of L'Heureux. Garrucci's extensive travels throughout Europe would culminate in a major publication on Christian art in the Late Antique and Early Medieval eras, the Storia della arte cristiana nei primi otto secoli della chiesa (6 vols, Prato 1873-1881).

Well before this monumental undertaking, Garrucci published the first detailed description of the Vigna Randanini excavations in 1862, and would go on to publish others until work in this first phase was suspended in 1865. His plan of the Jewish catacomb, depicting only those galleries excavated by early 1862, was the only one widely available before Fr. Jean-Baptiste Frey commissioned a new one for a 1933 publication on new inscriptions in the site. It is not clear if Garrucci, like de Rossi, was able to see the Jewish tombs in the nearby Vigna Cimarra, excavated in 1866, but it is certain that he closely followed developments in these sites for decades, both in Rome and at Venosa.

Figure 10. Entrance to the Catacomb of Vigna Randanini, an unexpected archive of Graeco-Roman Paintings (DAPICS n. 0080).

The next unexpected discovery of a Jewish catacomb took place on the via Casilina, the ancient via Labicana, in 1882, on the grounds owned by Roman lawyer Francesco Apolloni (or Apollonj). Apolloni intercepted a few cemetery galleries in the reactivation of a quarry near the roadside at the second kilometer from the city. Believing these to be Christian, he alerted the CDAS, and Marucchi came out to explore the site. In spite of the heavily damaged condition of the catacomb, Marucchi, with the aid of the excavator Luigi Caponi, accessed different galleries of the site and detected near an ancient staircase or other opening now choked with debris a partially intact loculus marked by the menorah motif. With de Rossi's encouragement, Marucchi lost no time in lecturing and publishing on the "new" Jewish catacomb of the via Labicana.[xxiii]

In this same time period, a German Protestant (Lutheran) student came to Rome on scholarship with the intent to study Jewish tombs and epitaphs. This was none other than Nikolaus Muller, the future excavator of the catacomb of Monteverde. Muller's first catacomb excavation in 1885 was on a property of Prince Alessandro Torlonia on the via Appia Pignatelli, in front of an entrance to the Vigna Randanini catacomb, but on the opposite side of the road. He believed this site also to be Jewish, though on very uncertain and circumstantial grounds. He was one of the few to actually see the Appia Pignatelli site before it was filled in once more, leaving his testimony unsurpassed to the present time.[xxiv]

In the twenty years between Roman catacomb excavations on the Appia and the Monteverde, Muller, now a professor of theology and Christian Archaeology in Berlin, tried to bring to completion a study on all the ancient Jewish cemeteries of Italy. In early November of 1904, when the manuscript was nearly ready after a prolonged sojourn in Venosa, Muller got word that Jewish tombs had emerged a few days before in a landslide on the Monteverde. He lost little time in inspecting the site in the company of CDAS officials Baron Rodolfo Kanzler and Augusto Bevignani. The catacomb’s exact position was revealed to be on a hillside about one and a half kilometers from the Porta Portese, on a branch road from the via Portuense known at that time as the via di Monteverde, in a property owned by the Marquis Pellegrini Quarantotto. Here, too, recent quarrying had put much of the site in an imminent danger of collapse.

Given the threat of the open quarries below the crumbling cemetery vaults, Muller considered the study of the site of the utmost urgency, and returned over several seasons with funding in part from the Akademie für die Wissenschaft des Judentums in Berlin (Berlin Society for the Advancement of Knowledge of Judaism) to dig out what was left of the cemetery and record its remains. The first series of excavations were conducted in 1904-1905 and continued in the spring and fall of 1906. The early campaigns confirmed that it was, indeed, the site that Bosio had first visited in 1602: the signature of his illustrator, "Toccafondo" was found on one of the tombs.

Figure 12 a-d. Four unique photographs of the interior of the now collapsed and non-existent Jewish catacomb of Monteverde from Nikolaus Muller's "Cimitero degli antichi Ebrei posto nella Via Portuense," Dissertazioni della Pontificia Accademia Romana d'Archeologia, Ser. II, v. 12 [published posthumously] (1915), (Tav. XI, XII) (DAPICS nn. 1421-1422).

1. Muller, in a series of excavations, uncovered eleven different types of tombs in this major archive of Jewish history. Two examples are illustrated in this view of a collapsed gallery; an open tomb in the floor and a loculus with epitaph painted on the lime of the closure.

1. Muller, in a series of excavations, uncovered eleven different types of tombs in this major archive of Jewish history. Two examples are illustrated in this view of a collapsed gallery; an open tomb in the floor and a loculus with epitaph painted on the lime of the closure.2. The doorway of a destroyed cubiculum opening off of a collapsed gallery perforated with loculi.

3. A menorah painted in red above a tier of loculi, in a collapsed gallery -reminiscent of Bosio's illustration.

4. A painted epitaph on the lime of the closure of a destroyed loculus, reads "Here lies Simon. In (peace) his sleep." Unfortunately, inscriptions like this could not be salvaged like their counterparts in stone, the majority of which were retrieved by Muller with the encouragement and assistance of the Commissione di Archeologia Sacra, the owners of the vineyard under which the Monteverde catacomb was situated, and the "Berlin Society for the Advancement of the Knowledge of Judaism".

Unfortunately, "insurmountable obstacles”, notably disputes with the landowners over accident liability and compensation, forced Muller to abandon the dig in 1907. He lectured on the results of his excavations in Rome in 1909, but died in 1912 before submitting his final report on the necropolis' structure and finds. Muller had sent to Marucchi a copy of his Rome lecture, which was published in Italian in 1915, after a similar German text had come out the year of Muller's death in 1912. The larger manuscript and study notes were left to Muller's legal heirs, his brothers, who turned over the material to a scholarly committee in Berlin consisting of Muller's colleagues, Professors Kawerou, Deissman, and Kurth. The decision was reached to keep Muller's archive in the offices of the New Testament Seminars, of which Deissman was director, at the Royal University of Berlin. Not long thereafter, recognizing the importance of this data, Kurth took on the initiative to publish the Judaic epigraphy. The committee then turned to the Wissenschaft academy, chaired by Dr. Martin Phillippson, to commission Dr. Nikos Bees, a former assistant of Muller, to complete and publish Muller's manuscript.

In 1913, Deissman, at the request of the noted Latin epigraphist Prof. Hermann Dessau, asked Marucchi to go ahead and publish the manuscript Muller had sent him of his Rome lecture. Marucchi, in turn, approached Deissman in 1914 for access to Muller's plans and other notes left in the estate, in view of the fact that the CDAS was now exploring another sector of the catacomb which had emerged after Muller's last dig in 1906. He arranged for Muller's Italian text to be published in 1915 as Muller had written it (Marucchi added to the end of Muller's publication an appendix of photographs of inscriptions, which had been sent to him by Muller though without instructions as to where they should be included). Marucchi, on his own part, was occupied with yet another role as special director of the Lateran Christian Museum where he was arranging the finds from Muller's excavations in a "Jewish Lapidary" or "Sala Giudaica" (the collection now displayed the Pio Cristiano Exhibit in the Vatican Museums). Part of the Lateran project was the publication of the epitaphs from the areas found in 1913, by "express desire" of the Prefecture of the Apostolic Palaces. A nephew of de Rossi, Giorgio Schneider Graziosi, catalogued and published the epitaphs, though the exhibit itself included a marble plaque crediting Muller's role and the gift of the collection to the Museum by the Pellegrini Quarantotti.

Schneider Graziosi's work led Bees to complain bitterly in a postscript to his own published study of the Jewish inscriptions in 1919 that Marucchi had betrayed a supposed agreement with Muller that no final version of the inscriptions would be published before Muller's own work was complete. Bees had been commissioned not by Muller directly, however, but by his benefactors at the Wissenschraft academy. Nonetheless, Bees believed he had cause to criticize the Italian publication for its many errors and contradictions, even making a personal attack on Schneider Graziosi, who Bees considered unfairly favored because of his close family connections to members of the CDAS. This last move aroused great anger among the Italians, since Schneider Graziosi was no longer alive to defend himself, having been killed in battle during World War I.[xxv] Bees' own publication, Die Inschriften der jüdischen Katakombe am Monteverde zu Rom, although favored with high quality with facsimile photographs of the inscriptions, was in turn criticized for its lack of content and especially "the very unjust villainy of the preface"... "an envious and graceless attack" on Marucchi and Schneider Graziosi. These are the words of the Italian archaeologist Roberto Paribeni, who would later be involved in cultural propaganda during the Fascist regime, and here, too, he hardly elevates the tone of the exchange by suggesting that part of the issue is due to Bees' "judicial bent of mind" and "own lands of origin" (Greece).[xxvi]

As noted, toward the end of 1913, a new sector of the Monteverde cemetery was revealed by chance in an adjoining property of the Rey family. Baron Kanzler wrote an official report on the investigation of the region by Enrico Josi and Schneider Graziosi.[xxvii] Again, the archaeologists were largely involved in a salvage operation in the site, which had already been exposed and was now in imminent danger of collapse. The artifacts joined the others from Monteverde in the Lateran Museum's Jewish Lapidary and Schneider Graziosi completed his documentation of the exhibition with the altruistic statement that "all the scholars should be grateful to the Prefecture of the Apostolic Palaces and to the administration of the museums for having added this very important epigraphic group to the notable Christian Lateran collection, an appropriate location because of the close relationship between the Jewish monuments and those of primitive Christianity”.[xxviii]

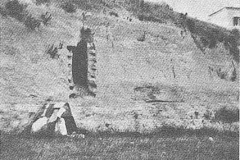

The last documented activity on the Monteverde cemetery was in 1919, This time, however, perhaps in light of the circumstances which brought about the find, on land being developed for government housing, it was supervised by an archaeologist of the State, Roberto Paribeni, who was overseeing the excavation of another Jewish catacomb complex the same year on the via Nomentana, on the property of Prince Torlonia. The twenty-four inscriptions recovered in the rescue operation on Paribeni’s watch were taken not to the Lateran’s Jewish Lapidary but to the National Roman Museum at the Baths of Diocletian. The number of epitaphs copied from the Monteverde catacomb now numbered a little over 200, representing the largest quantity of inscriptions from any one Jewish site in Rome. A little over a decade after Paribeni's study, on October 14, 1928, a landslide buried the access to remains of the site.

Figure 13. A short, sheared-off impassable sector of a gallery with loculi, one of the few vestiges still remaining in 1919 of the Catacomb of Monteverde which was sliding into a declivity on the hill due to continuous quarrying activity over the centuries. From Roberto Paribeni, "Iscrizioni del cimitero giudaico di Monteverde," in Notizie degli Scavi d' Antichita', 1919 (DAPICS n. 3635).

The other Jewish cemetery studied by Paribeni in 1919 – to date, the last "new" discovery of an ancient Jewish site in Rome - was on the other side of the old city - on the first kilometer outside of the Porta Pia on the via Nomentana. It had been unearthed by laborers trying to repair the sagging foundations of stables on the grounds of the Villa Torlonia. To that time, the site had not been thought to be Jewish, but then it was remembered that de Rossi had suggested the existence of a Jewish cemetery in the area between the via Nomentana and via Tiburtina as far back as 1865, based on his interpretation of the mention of a Jewish prayer house or proseucha in the text of a pagan epitaph (CIJ 1.531), which located the structure by the Esquiline agger.[xxix] This non-Jewish Latin inscription is dedicated to Publius Corfidius Signinus who sold fruits in a stall near the proseucha (synagogue) near the agger. There is not definite proof it was administered by a named Jewish congregation, like that of the Siburesians, but we know from epitaphs that at least four members of that particular congregation were buried in the Torlonia catacombs. Prince Giovanni Torlonia, a senator of Italy, financed the excavation of the catacombs, which was conducted by Torlonia's staff engineer, Agostino Valente, and carried out by the prince's own laborers, all under Paribeni's supervision on behalf of the Royal Superintendence of Excavations.[xxx] The work went on until the catacombs’ extent was known, and the prince could find surer foundations for new buildings on his estate: he balked, however, at the cost of shoring up the site as an archaeological display. The scope of the Torlonia project is revealed in the architect Italo Gismondi's plan, published with Paribeni's preliminary report in the government archaeology bulletin, Notizie degli scavi d'antichita' in 1921. Gismondi here maps out an extensive cemetery on two levels, in all likelihood two separate catacombs that were later joined, as excavations fifty years later would show beyond a doubt.[xxxi]

Figures 16-17. The grounds of the Villa Torlonia before it became a public park (DAPICS nn. 0677, 0679).

Prince Torlonia did allow two German scholars, Hermann W. Beyer and Hans Lietzmann, to study the site and make a new plan and photographic record of its structural elements, paintings, and finds.[xxxii] The German project began in the spring of 1925 and the report came out five years later, in 1930. Beyer wrote on the topography and structure of the Jewish catacombs: Leitzmann on the paintings, the inscriptions, and the rest of the artifacts. Over the course of his investigation, Beyer had been able to access the lower catacomb almost completely, but the upper catacomb remained blocked in many areas, or possible to enter only by crawling on one's stomach over piles of dirt, including the only point at which the two catacombs connected.

Not long after the Villa Torlonia catacombs were closed to visitors in 1925, once Mussolini - ironically enough, in light of his racist policies and collusion with the Nazis - made the estate his family residence in Rome, and the Monteverde catacomb slid once again into oblivion, although in 1929, the Italian government, as an afterthought to lengthy treaty negotiations with the Holy See, handed the Jewish catacombs over to the latter, along with rights to administer the ancient Christian catacombs and their shrines. For the next six decades after the signing of this “Lateran Pact”, de Rossi's old commission, now reconfigured as the Pontifical Commission for Sacred Archaeology (PCAS), would safeguard the surviving Jewish catacombs of Rome until a treaty revision would return these sites to the government of Italy in 1984, though the official consignment of the Vigna Randanini and Villa Torlonia catacombs would not be made until 1984 and 1988, respectively.

The PCAS soon acquired dozens of new sites to investigate, clean, and restore in the wake of new waves of (sub)urbanization, and consequently lacked both the human and financial capital to make major structural improvements to the Jewish catacombs of Rome, situated on private estates and only accessible with permission. The largest projects in these sites during the post war period took place between 1972-1974, when the Vigna Randanini and Villa Torlonia catacombs were both restored, the latter quite drastically, on its upper level, where new excavations revealed a second entrance to the catacomb and artifacts including inscriptions, sarcophagus fragments, and grave goods. The work in both sites was carried out by the newly-appointed Secretary of the Pontifical Commission for Sacred Archaeology, the Barnabite priest Fr. Umberto M. Fasola. Fasola's overarching plan was to document all the catacombs under Vatican jurisdiction, but he went further in the Villa Torlonia site between November, 1973 and June, 1974 to thoroughly disinter and explore all the known subterranean galleries at the southwest corner of the Villa Torlonia. This PCAS project provided not only a more accurate plan, especially of the upper galleries and peripheral areas of the lower level, but also clarifications as to the origins and development of the Jewish cemetery, which was proven beyond a doubt to be the result of the linking - perhaps accidentally - of two separate catacombs, each with its own access and unique phases of development.[xxxiii] Out of concern for the lack of security at the site, expropriated from Torlonia's heirs not long after his dig, Fasola went ahead and issued the controversial order in 1978 that all entrances to the Jewish cemetery be backfilled until proper maintenance and security measures guaranteed its protection.

The period following the Second World War brought more discoveries of catacombs of Rome that contributed toward a better understanding of the Jewish burial sites in terms of structural development, ownership, and visual effects. One site in particular, while not likely to be Jewish, showed Jews as protagonists of important Biblical scenes. In 1955-1956, under the direction of Fr. Antonio Ferrua, SJ, Fasola's predecessor at the helm of the PCAS, and the construction engineer Mario Santa Maria, the commission excavated a previously-unknown catacomb on the via Latina. The spectacular paintings in its crypts had not been noted by previous catacomb explorers, probably because the site was not mentioned in pilgrimage accounts and did not appear to contain any venerated tombs. When Santa Maria, driven by simple curiosity to see what the builders had found, lowered himself into the drill hole which had been churning up fragments of painted plaster, he was simply astounded at the size and ornamentation of the subterranean rooms.[xxxiv] The catacomb of the via Latina (or of via Dino Compagni), in fact, would contain several paintings that in subject were rare or unique to catacomb art, including vivid depictions of episodes from the Hebrew Bible, all dated to the fourth century CE.

Figure 18. Site of the Catacomb of via Dino Compagni below modern streets and apartment buildings at the juncture of via Dino Compagni and the via Latina in Rome (DAPICS n. 1844).

[i] G. B. de Rossi, Roma Sotterranea, 1 (Rome, 1864), pp. 2-9; P. Testini, Le catacombe cristiane a Roma (Bologna, 1966), p. 15.

[ii] Testini, Catacombe cristiane, pp. 15-16.

[iii] De Rossi, Roma sotterranea cristiana, 1, pp. 9-11.

[iv] C. Baronius, Ann. ad an. 57, Section CXII, 130; Section III, 226; Section VIII, IX, all cited in de Rossi, Roma Sotterranea, p. 13.

[v] J. Stevenson, The Catacombs: Life and Death in Early Christianity (Nashville: T. Nelson, 1978), p. 51.

[vi] According to ancient tradition, the Ostriano cemetery was where St. Peter used to baptize: de Rossi, Roma Sotterranea, 1, p. 20.

[vii] F. Mancinelli, Catacombs and Basilicas of the Early Christians in Rome (Florence: Scala, 1981), pp. 45-46.

[viii] De Rossi, Roma Sotterranea, 1, p. 13.

[ix] De Rossi, Roma Sotterranea, 1, pp. 26-26.

[x] De Rossi, Roma Sotterranea, 1, 26-27.

[xi] H; Leclercq, Manuel d'archéologie chrétienne depuis les origines jusqu'au VIIIe siècle, 1 (Paris, 1907), p. 21.

[xii] De Rossi, Roma sotterranea, 1, p. 31.

[xiii] Bosio, Roma Sotterranea, p. 125; P. Testini, Catacombe cristiane, p. 20.

[xiv] M. N. Adler, The Itinerary of Benjamin of Tudela (New York: Phillip Feldheim, Inc., 1907), pp. 5-9.

[xv] The Latin version of Migliore's account is published by J. B. Frey in the Corpus Inscriptionum Judaicarum, 1, p. 207. The English version used here is a free translation.

[xvi] G, Migliore, Ad Inscriptionem Flaviae Antoninae Commentarius sive de Antiquis Judaeis Italicis Exercitatio Epigraphica: prolegomena, Cod. Vat. Lat. 9143, f. 127, b. Author Estelle Brettman noted that she was "grateful to Prof. Mason Hammond and Joseph Horn for help with the interpretation of these difficult passages".

[xvii] R. Lanciani, New Tales of Old Rome (Boston: Houghton, Mifflin, 1901), p. 247.

[xviii] H. J. Leon, "The Jewish Catacomb Inscriptions of Rome: An Account of their Discovery and Subsequent History," in Hebrew Union College Annual, 5 (1928), p. 307.

[xix] Testini, Catacombe cristiane, p. 29.

[xx] Four years earlier, in the vineyard above, de Rossi had discovered one fragment of the marble inscription which was engraved with the name of this pope, which fit later with other fragments of the same epitaph found in the Lucina crypt: de Rossi, Roma Sotterranea Cristiana, 1, pp. 275-305.

[xxi] De Rossi, Bollettino di Archeologia Cristiana, 5.1 (1867), p. 3 and 16 (plan). See also J-B. Frey, CIJ 1 nn, 277-281a.

[xxii] O. Marucchi, Le catacombe romane (Rome, 1903 (rev. ed. Enrico Josi, 1933), p. 676. E. R. Goodenough, Jewish Symbols in the Greco-Roman Period, v. 2 (New York: Pantheon Books, 1953), p. 15, also dates the discovery of the Vigna Randanini catacomb to 1857.

[xxiii] O. Marucchi, "Di un nuovo cimitero giudaico scoperto sulla Via Labicana," in Dissertazioni delta Pontificia Accademia Romana di Archeologia 2.2 (1884), pp. 497-532.

[xxiv] N. Muller, "Le catacombe degli Ebrei presso la via Appia Pignatelli," in Römische Mitteilungen, 1 (1886), pp. 49-56.

[xxv] R. Paribeni comments on the rivalry as perhaps being due to the "excitability of the war period" in "Iscrizione latina del sepolcreto giudaico di Monteverde," in Notizie degli scavi di antichita' (1921), pp. 358-359, n. 2.

[xxvi] Paribeni, "Monteverde," pp. 358-359, n. 2: Paribeni goes on to say that "to claim a that a director of a Museum (Marucchi) would leave unpublished a collection in his museum for eleven years after the discovery (of the Monteverde catacomb, in 1904) and three years after the death of the discoverer to respect the intentions of presumed heirs who had given (Bees) the material and means for his study and to sustain this pretension has the ring of villainy and is grossly unjust".

[xxvii] R. Kanzler, "Scoperta di una nuova regione del cimitero giudaico della via Portuense," in Nuovo Bullettino di Archeologia Cristiana 21 (1915), pp. 152-157.

[xxviii] G. Schneider Graziosi, "La nuova sala giudaia nel Museo Lateranense," in Nuovo Bullettino di archeologia cristiana 21 (1915), p. 56.

[xxix] De Rossi, Bullettino di archeologia cristiana 3.12 (1865), p. 95.

[xxx] Estelle Shohet Brettman noted in her manuscript that "the history of nineteenth and twentieth century excavations of Jewish sites in Rome is particularly tied to the Torlonia family. In fact, the present Prince of Torlonia has been extremely helpful in assisting me with my work".

[xxxi] R. Paribeni, “Catacombe giudaiche sulla via Nomentana,” in Notizie degli Scavi d'antichita' 17 (1920), pp.143-155.

[xxxii] H. W. Beyer & H. Lietzmann, Die jüdische Katakombe der Villa Torlonia in Rom (Studien zur spätantiken Kunstgeschichte 4) (Berlin-Leipzig: Walter de Gruyter, 1930).

[xxxiii] U. M. Fasola, “Le due catacombe ebraiche di Villa Torlonia”, in Rivista di Archeologia Cristiana, 52 (1976), pp. 7– 62.

[xxxiv] A. Ferrua, Le Pitture Della Nuova Catacomba di Via Latina (Rome: Pontificio Istituto di Archeologia Cristiana, 1960), p. 9.

The summertime is synonymous with adventure, exploration, and new experiences for children. It's the perfect season for parents to look into opportunities that can provide their kids with both fun and educational value. One of the most sought-after experiences in this regard is the Kids Summer Camp, where children can make lasting memories while developing important life skills. https://pilotparenting.com/

Many parents recall their own childhood memories of summer: the friendships made, the games played, and the tales of campfires under starry skies. Wishing the same for their children, they often turn to the age-old tradition of the Kids Summer Camp. This immersive experience promotes personal growth, introduces kids to new hobbies, and ensures they return home with stories to last a lifetime.