Journalist Sara Toth Stub interviewed ICS director Jessica Dello Russo for the article, "Secrets of the Catacombs" in the January 2024 issue of Archaeology Magazine. Below is the complete transcript of her interview with Dr. Dello Russo on 6 September 2023, quoted in part.

STS: What is the overall significance of the Villa Torlonia catacombs? Are these different from other Jewish catacombs in Rome?

JDR: The catacombs of Villa Torlonia are located about a kilometer from the ancient walls of Rome, near the ancient trajectory of the via Nomentana and a crossing, similar to the via Spallanzani of today. Several historic or named Chrisitan cemeteries were on the same highway, including one now open to the public at Saint Agnes Outside-the-Walls. I mention the Christian sites to emphasize that the Jewish catacombs of Villa Torlonia, while apparently self-enclosed and not known to connect to other cemeteries or tomb enclosures in the surrounding terrain - although the actual terminus of a small number of galleries is not yet known - would have been located in the general area of a Roman-era roadside necropolis, not exclusive to Jews, although nothing of this ancient development is currently visible in the site. The land has been a public park only since 1978 - before then, for nearly two centuries, it was extensively landscaped and built upon by the Torlonia family as a showpiece estate - with conspicuous fake ruins, even a modern cave decked out to look like an Etruscan tomb. Whether or not the family was actually aware of the catacomb is not clear, but we know that they closely controlled their public image, and tried to suppress the rumor that, because of their non-Italian origins and extreme wealth, they were converted Jews. The Jewish artifacts reportedly in their possession - in what became and still remains one of the largest privately-owned collections in the world of ancient art - remained for the most part unpublished until the early twentieth century, and nearly all are unaccounted for today. When the Jewish catacombs were finally revealed in a building site on the property in 1919, Giovanni Torlonia, who later rented the estate to Mussolini, made a point of saying that he regretted that they had not turned out to be Christian.

The overall significance of these underground cemeteries for Jews is that they are virtually the only surviving testimonies of a distinctly Jewish material culture in Ancient Rome that employs pretty much the same motifs and expressions seen as markers of Jewishness in all parts of the Late Ancient Mediterranean and beyond. Artifacts labeled with the representative menorah, sometimes accompanied by other emblems of Jewish ritual practice, have come up in other sites around the city, even the Palatine itself, but the catacombs have produced the bulk of the information for what is currently known about Jews in the city itself - although the archaeological traces of a synagogue complex in nearby Ostia Antica have helped to flesh out some of the context of Jewish communal activity that is still missing from Rome itself. We wouldn't know about these people or even the names of the synagogues they frequented without the evidence from the Jewish catacombs. Literally, they make history.

What makes the catacombs of Villa Torlonia quite special can be expressed in terms of the nicknames given by modern excavators to the two distinct excavation projects that over time created the cemetery network that we see today, each one excavated from its own entrance point into a different level of the underground. One region - two regions, actually, but both depending on one point of entry - was known as the "catacomb of inscriptions" and the other was the "catacomb of the pictures". The inscriptions, many painted directly onto the rubble and mortar seals for the shelf-like tombs, and written for the most part in Greek, give us personal names, loving attributes, good wishes and blessings, and, in some instances, community office titles, including one still very debated term that could be read as the "archigerusiarch", maybe the leader of an assembly of elders. There is even some evidence of Hebrew, which is actually quite rare to find in epitaphs made in Rome during this period, although all the cemeteries in question have been heavily vandalized. An early visitor to the newly-discovered site in the 1920s, the American Classicist and Reform rabbi Harry J. Leon put it this way: It was deeply moving for him to read the epitaph of a Jewish woman from almost two thousand years ago and still see her bones right there in the tomb. Like Leon, Jews today feel strongly about this evidence of a continuous presence of Jews in Rome in light of so many centuries of oppression to the point of near-elimination in very recent times.

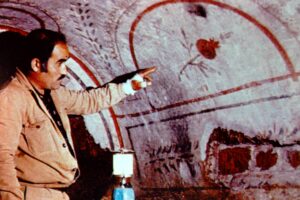

The wall paintings in the other region of Villa Torlonia are even more extraordinary, and it is really necessary to see them in person to appreciate the brilliant colors and vivid style of depicting for the most part Jewish motifs connected to synagogue liturgy and annual festivals like Rosh Hashanah and Tabernacles. Pictures, even photographs depending on artificial lighting, don't do them justice! We don't know at present who was originally buried in these beautifully decorated tombs, all found in one gallery near the staircase to the grounds above. The tomb style is that of the fourth century CE, so these are individuals who lived in a time when Christianity was becoming more and more of a public institution in Rome. The level of tomb decor would indicate Jews of means, perhaps patrons of their community, but, as time went on, the painted tomb niches themselves were filled up nearly to the top with later tombs so that little of the original decoration could be seen until modern excavators removed the walls of the later tombs and exposed the paintings once more.

The Villa Torlonia catacombs also have some very distinct features in their planning and tomb design. Even within the site itself, there are marked differences in appearance between regions: why, exactly, I don't know, maybe there was a different dig crew employed or a different plan adopted to sell off burial spaces within the site. The upper galleries have around thirty tall arched wall recesses; the lower galleries virtually none, unless you count those with a very low arch, part of an arrangement when more than one burial was made in a single wall slot. The lower regions also exist side by side, but were originally excavated separately: that is, a landing was created within the original access stairway from the ground to area E to allow for a branch staircase to lead into a whole new network of galleries (area D). This might indicate a permission or land acquisition to expand into the zone, but it is interesting to see that access to both regions was through this one stairway, only. But it is hard to read a "Jewish" meaning into elements of structural design: it might have more to do with property limits, pre existing tunnels, and other circumstances.

Regarding its design, the catacombs of Villa Torlonia have a number of features in common with non-Jewish catacombs in the areas northeast of Rome along the via Nomentana and elsewhere: including the marking up of some of the gallery walls with designs in lime to map out the burials and intersections and the frequent use of very basic materials to seal up the tombs. The diggers knew what they were doing. The site might even have been a prefab arrangement on the part of cemetery developers which Jews were able to obtain for use by members of their community, as there are signs especially in the upper catacomb that a lot of the monumental space was never really used to its full potential in terms of the added expenses of tomb style and decor, and later extensions of galleries in the site show a more haphazard type of tomb distribution. A lot of the tombs were created in a very simple style, wall slots closed by masonry. This was carried out very carefully and in many galleries with great regularity as to the size and spacing of the wall slots. These details help to read a very interesting history of development of the site. All the same, there is no question that all the spaces created were ultimately used for the burial of Jews - if there were "interlopers", that would be at a late date, as might be the case for a tomb made in one of the stairwells, and the presence of lamps with Christian symbols like the Chi-Rho might just point to the sheer necessity of artificial lighting in the complete darkness of the catacombs - anything that was handy, as the Chi-Rho style certainly was. There were also small objects attached to some of the wall tombs that were clearly personal objects and on the whole not associated with Jewish ideas in any way. That being said, the clientele for the Villa Torlonia catacombs were Jews seeking burial next to other Jews - as is sometimes spelled out in the epitaphs their wish was to sleep "among the holy ones" or "among the just" . They are remembered in terms of their goodness and generosity toward the community, and love of the Law.

STS: Are Jewish catacombs in Italy well-understood, or are there many questions remaining?

JDR: The big elephant in the room is - accessibility! There are Christian catacombs regularly open to the public at around 10 euro. To enter the only Jewish catacomb in Rome currently open to the public, in the former site of the Vigna Randanini, one spends more than ten times that, unless one has the opportunity to join a guided tour of up to 15 people. Ideally, a public monument should not cost so much to tour - but the catacomb in question is on the grounds of a private property and a custodian must be paid to open the site. The Villa Torlonia arrangements promise to be quite different, although to date the catacombs themselves remain off limits to all but the most privileged insider. From what I understand, the Jewish community of Rome hopes to train its own guides to work at the site, similar to what you would find in many of the other catacombs in Rome open to the public. In a somewhat ironic twist, Mussolini's underground bunker in the Villa Torlonia was open to the public before the cemetery was: of course, it is smaller, of fairly recent construction, and does not contain bones!

For those specialists fortunate enough to be able to examine the Jewish catacombs and any material removed from them in the past - mainly to museum galleries and storerooms - there are, indeed, big questions to be addressed and next steps to take. At the top of the checklist, making images of the inscriptions and of other cemetery features widely available. Even if the archaeological authorities don't want Jewish catacombs turning into another Coliseum of tourism - being wholly underground, their microclimate simply can't handle that volume of visitor traffic, and people throughout the centuries have had a bizarre tendency to steal the bones - there are no negative and invasive consequences in providing digital reproductions of the artifacts, many of which still await publication. Recent study of the Jewish catacombs of Venosa by the University "L'Orientale" in Naples under the direction of Prof. Giancarlo Lacerenza is a good example of systematically documenting the architecture and artifacts and rendering this material open access.

The fact is, without targeted investment in Geo Radar surveys, 3D mapping and other strategic approaches, and - yes, ground excavation and historical osteology analysis - remember, a rabbinical ruling has allowed this now to be done on human teeth - there is a lot of information that will continue to escape us. It's not just the cost of highly specialized labor and instruments. The problem also involves the reality that many Jewish catacomb sites are on privately owned land, and, apparently the property owner still has a lot of influence over what can take place. These private citizens are legally bound not to further obscure or cause deterioration to the monument in question. At the same time, and perhaps understandably, they don't appear to welcome the disruptive presence of tourists. Even so, this sense of ownership over the site has frustrated serious study - nothing like having a guard dog or an untethered bull going at you to force a quick exit!

Leaving aside for the moment the question of the origin of this type of cemetery development in Rome - we'll speak more about that in a minute - beyond better documentation of and accessibility to these sites, they should not be studied in a "bubble", that is, just as information about Jews. These people represent Ancient Rome. Don't take the statistics from these burial grounds as exclusive indicators of the community - they were part of a civil society and were representative of it as well. And it's pretty clear that not all Jews were buried in catacombs!

STS: Is it possible to say where the origin of catacomb burials in Rome comes from? Does this come from Jewish practice?

JDR: I've traveled to the Middle East and other parts of Italy to consider this issue carefully, being aware of my own bias in the matter, having been trained in the Vatican's archaeology program, from which I obtained a Ph.D. in archaeology in 2022. My take after studying examples of rock-cut tombs for Nabateans, Jews, Phoenicians, and other Semitic communities, and those of different communities on the Italian peninsula and islands, is that local know-how created the catacombs on the scale that we know them today - notably those reaching truly colossal dimensions after being developed on multiple levels, with interior connections as well as external points of access, often from pre-existing tomb enclosures, used for hundreds, then thousands, then tens of thousands of burials if not more. Given the land use already where we find catacombs, it would have to be something of an entrepreneurial opportunity more than a cultural or ideological choice - although it might be a combination of the two. Rome's malleable volcanic soil provided the opportunity to carve out and articulate tomb designs in amazing ways, with many options for customization for familial or other group aggregations, as we see just in the Jewish catacombs alone. The "fossores" or gravediggers provided these services, and it was a real business. The Jews of Villa Torlonia had access to this type of specialized labor, and furnished the site according to their needs and circumstances. Other underground cemeteries used by Jews in Rome have very different layouts and tomb designs, although with many points in common, including the epigraphic language and overall concept design. This type of rock-cut burial enclosure was made in different areas of Italy in suitable geological strata centuries before the catacombs came into existence. However, it was on a far more limited scale, more in line with what was being also done in the Mediterranean East for families of means. In fact, some catacomb areas connect with or develop from similar "closed" tomb networks for intimate use that date from perhaps the end of the second century CE, certainly by the first decades of the third. The structural evidence suggests that Jews and Christians adopted the "open" style catacomb with less hierarchical distinctions, a certain monotony of planning, if you like - around the same time, within the chronological framework cited above. I know there have been radiocarbon dating experiments that suggest otherwise for Villa Torlonia, and I have my fingers crossed that the recent excavations in the site to open it to the public on the part of Rome's Archaeological Superintendency have included the careful recording and analysis of the entrance points in order to provide the necessary data as to the sequence of building in the site - otherwise the "primacy" of the Villa Torlonia catacombs must remain in my mind a theory.

STS: I would like to speak briefly about the history of the Jewish community in Rome, especially during Late Antiquity----and how Jewish catacombs help us understand this time period.

JDR: As I said, the catacombs pretty much provide what we know about Jews in late ancient Rome, with the synagogue and tomb markers from nearby Ostia important points of confrontation. Again, it's important not to see this evidence as monolithic - in fact, as is oft-repeated in specialist studies, had we not found certain epitaphs in a Jewish catacomb site, it would be well-nigh impossible to consider them within the corpus of Jewish epigraphy. Maybe for this very reason, despite the presence of Jewish cemeteries in different areas of the suburbs of Rome, we're missing so many Jews, especially from the late republican and early imperial eras, when they are already documented as living in the city, because they were buried in so-called "neutral" settings and what we commonly call "catacombs" did not yet exist. Seeing catacombs as a developing trend in late antiquity reminds us to open our eyes and our minds to finding Jews in other places - not as "lapsed Jews" or as "assimilated Jews" but Jews in virtually all sectors of Roman society, as they seem to have been. Because of their position well below ground, the catacombs kept their structural integrity somewhat more complete than that of many structures at or near surface level. The type of information we can retrieve from them is what under most other circumstances would not have survived.

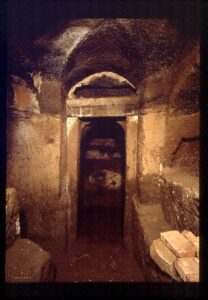

Terminal point of a gallery closed off in wall of masonry in the lower catacomb of Villa Torlonia, Rome.

Detail of a wall tomb with an arched roof in a gallery of the lower catacomb of Villa Torlonia, Rome.